Battle Analysis: Reconnaissance and Security Fundamentals at Chancellorsville

When a reporter was asked why so little was written about the work done by the cavalry during the Civil War, he said, “They were generally so far to the front, and so near the enemy, that it was rather dangerous – and unpleasant – to be with them.”1 This was certainly the case for the cavalry and scouts of the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia during the Battle of Chancellorsville – perhaps more so than during any other engagement of the Civil War.

During the battle, MG Joseph Hooker, commander of the Union’s Army of the Potomac, remarked in a telegram to MG John J. Peck: “So much is found out by the enemy in my front ... that I have concealed my designs from my own staff.”2 The Confederate cavalry’s application of the fundamentals of reconnaissance and security – in particular, ensuring continuous reconnaissance, retaining freedom of maneuver and providing early and accurate warning – allowed GEN Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia to defeat a superior force at this famous encounter.

Battle of Chancellorsville

The American Civil War had been dragging on for more than a year and a half by December 1862. MG Ambrose Burnside, at that time the commander of the Army of the Potomac, launched an attack against Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia across the Rappahannock River in Fredericksburg, VA.3 The Confederates halted the assault and drove the Union Soldiers back across the river, but the harsh winter weather made it impossible for Lee to counterattack.4 The two armies developed an unofficial truce to wait out the winter months since it was too cold for either side to continue offensive operations.5 During this time, President Abraham Lincoln relieved Burnside and replaced him with Hooker, who devised a plan to flank Lee’s army from the west once warmer weather came at a place called The Wilderness near Chancellorsville, VA.6 The warmer weather and operations for both sides commenced in early May 1863.

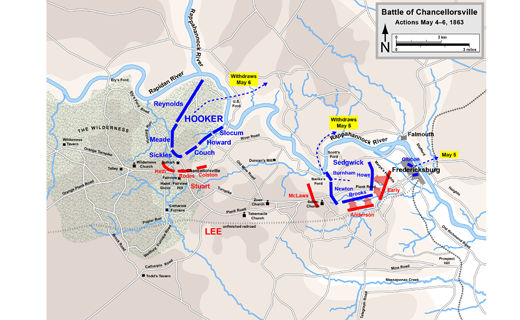

At 5 p.m. May 2, 1863, LTG Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson turned to one of his division commanders, BG Robert E. Rodes, and asked, “Are you ready?” After Rodes promptly answered, “Yes, sir,” Jackson ordered, “You can go forward, then.”7 With that, Jackson’s II Corps, comprising nearly 27,000 Confederates, began advancing.8 Jackson’s forces clashed with men of the XI Corps, making up the right flank of the Army of the Potomac, at Talley’s Farm, west of Chancellorsville.9 This fatal blow to an unsuspecting enemy was so severe that it sent the Union soldiers retreating north back across the Rappahannock River in the subsequent days. The Battle of Chancellorsville is known as Lee’s masterpiece as he, with the help of competent generals like Jackson and MG J.E.B. Stuart, with his band of mounted cavalrymen, defeated a force nearly double the size of his own.10

Confederate scouts proved invaluable to Lee early in the campaign. Hooker had ordered two corps, under MGs John Sedgwick and John F. Reynolds, across the Rappahannock just east of Fredericksburg in a feint April 29.11 The plan was to make the Confederates think this was the main body of the attack, then surprise them on their left flank with the rest of the Army of the Potomac. The trickery seemed to work at first, as Reynolds reported that “a demonstration will bring on a general engagement” and Sedgwick concluded that “the enemy seems to be in heavy force in [our] front. ... We are ready for them.”12 In a note from CPT William L. Candler, one of Hooker’s aides-de-camp, to MG Henry W. Slocum, commander of the XII corps in Chancellorsville, Candler wrote, “The general [Hooker] desires that not a moment be lost until our troops are established at or near Chancellorsville. From that moment all will be ours.”13

Lee, however, had been getting reports from the commander of his two cavalry brigades, Stuart, informing him of Hooker’s arrival in Chancellorsville and enemy movements against Stuart’s operations there.14 Elements of Stuart’s cavalry, COL John R. Chambliss’ 13th Virginia, disrupted parts of the Union army’s move south of the Rappahannock River near Brandy Station, northwest of Chancellorsville. Chambliss’ cavalrymen would fight, displace and fight again for more than five hours. During their engagements, they captured men from each of the three corps Hooker had sent across the river to flank the Confederates from the west.15 Lee concluded in a message to President Jefferson Davis that their “object [is] evidently to turn our left.”16

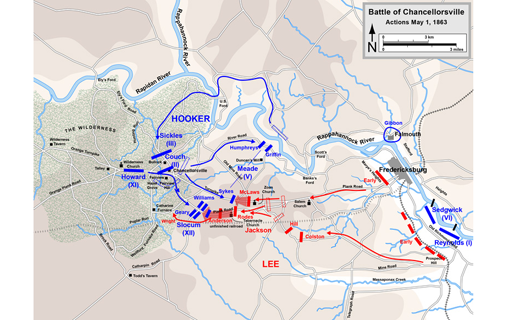

On the morning of May 1, word came from Stuart to Lee via courier that the enemy was advancing toward Lee’s left flank on the old turnpike and Plank Road.17 Armed with these scouting reports and believing, along with Jackson, that it would be “inexpedient” to attack at Fredericksburg, Lee issued Special Orders No. 121, which split his army into two parts.18 One division and one brigade (about 10,000 men) would remain near Fredericksburg under command of MG Jubal Early, while the rest of the army went west to check Hooker’s main advance near Chancellorsville.19

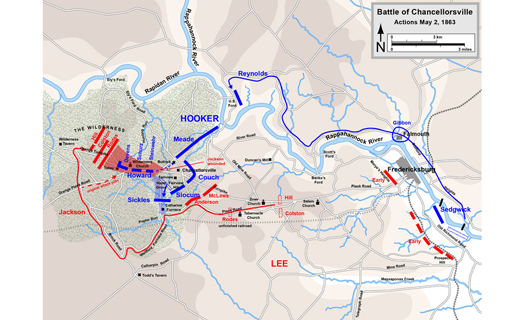

By the evening of May 1, Hooker had Lee’s entire army between his own two flanks, had him outnumbered two to one, and had more guns and supplies.20 At sunset, Lee and Jackson met on the Plank Road-Furnace Road junction to discuss their plans for the next day.21 They both understood the importance of regaining the initiative if they were to have any hope of success against the superior force, but knew of no way to get it. Finally, Stuart rode up with intelligence from his scouts. Stuart informed the other two generals that Hooker’s western flank was hanging “in the air” with no obstacles protecting it.22 That night, Jackson sent a local reverend with his topographical officer, MAJ Jed Hotchkiss, to locate suitable routes for a flank attack.23

Early May 2, Lee sent Jackson west around the enemy’s right flank with almost 27,000 men, leaving himself only 17,000 to face the main front of Hooker’s army south of Chancellorsville.24 The Confederate cavalry continued to prove its worth as BG W.H.F. “Fitz” Lee covered Jackson’s movements by “neutralizing [MG George] Stoneman’s ten thousand” with his brigade of Virginia horsemen.25 This cover allowed Jackson to make a 15-mile circuitous march around the enemy’s right flank virtually undetected.

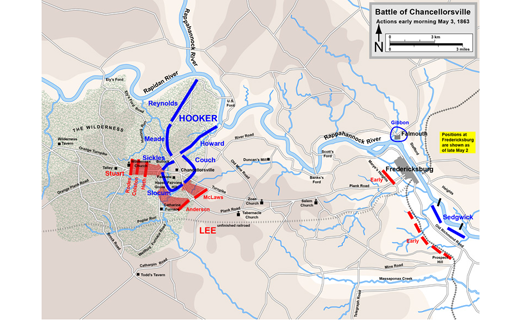

Jackson arranged his divisions carefully for the attack. He put Rodes’ division in the front, followed by BG Raleigh E. Colston and MG A.P. Hill, with Stuart’s cavalrymen protecting the corps’ right flank.26 The Confederates charged east into an unsuspecting XI Corps. Union soldiers were cooking their dinners and relaxing on bedrolls when they saw the Confederates come through the trees to their west.27 The 41st and 45th New York regiments, completely surprised, turned and ran without firing a shot. Union artillery only fired two rounds before being overrun.28 Attempts to halt the Confederate attack proved futile. Within an hour and a half, Jackson’s men drove the XI Corps more than a mile from its original position and were within two miles of Hooker’s headquarters.29

The assault halted around 9 p.m. as both sides reformed their lines. Jackson used this time to reconnoiter the newly formed Union line to identify a weak spot on which to concentrate his next assault. Unfortunately, Jackson was mortally wounded by gunfire from his own men during this reconnaissance – it would be up to Stuart to assume command and continue the attack.30

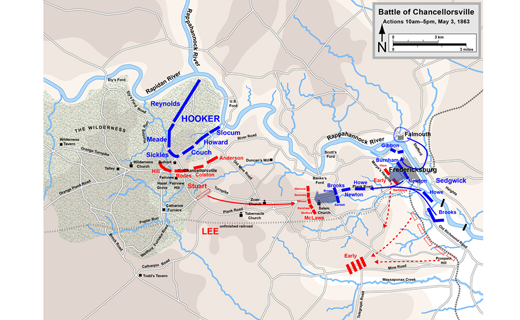

Stuart initiated the second wave of attacks early on the morning of May 3 to take two pieces of key terrain just west of Chancellorsville: Hazel Grove and Fairview Knoll. Capturing these pieces of terrain would link the right flank of Stuart’s forces with the left flank of the rest of the Army of Northern Virginia.31 Although costly, the fight allowed the Confederates to drive the Union back and reunite the flanks of the Army of Northern Virginia, forcing Hooker to take up defensive positions between Chancellorsville and the Rappahannock.32

Realizing the extent to which his forces had been surprised and overrun, Hooker ordered his army to abandon Chancellorsville on the night of May 4.33 Less than 36 hours later, the last Union soldiers crossed back to the north side of the Rappahannock via the U.S. Ford. The Battle of Chancellorsville ended, claiming the lives of more than 17,000 Union soldiers and nearly 13,000 Confederates.34

Application to contemporary doctrine

Understanding how the Confederate commanders recognized and accomplished their tactical requirements helps us learn more about our contemporary doctrine. According to Army Doctrine Reference Publication (ADRP) 3-90, the fundamentals of reconnaissance and security are the following: ensure continuous reconnaissance; do not keep reconnaissance assets in reserve; orient on the reconnaissance objective; report information rapidly and accurately; retain freedom of maneuver; gain and maintain enemy contact; develop the situation rapidly; provide early and accurate warning; and provide reaction time and maneuver space.35 At the Battle of Chancellorsville, the Confederate cavalry scouts most notably practiced three of these fundamentals by ensuring continuous reconnaissance, retaining freedom of maneuver and providing early and accurate warning.

Continuous reconnaissance is the ongoing collection of information about the enemy and terrain that supports the unit’s attempt to determine the enemy’s course of action.36 There are three examples from the Battle of Chancellorsville that prove the Confederates understood the concept of conducting continuous reconnaissance. The first occasion occurred April 29 when Stuart’s men discovered elements of the Union army advancing west toward Chancellorsville from Fredericksburg. Because they were actively conducting reconnaissance against the enemy, the Confederate scouts were able to discover Hooker’s true scheme of maneuver: to feint in Fredericksburg and flank the Confederates from their left.

The second instance in which the Confederate scouts demonstrated their understanding of ensuring continuous reconnaissance was on the evening of May 1, when they discovered the enemy’s right flank was weak with no obstacles protecting it. After determining the location, composition and disposition of the enemy, Stuart’s cavalrymen did not stop. Instead, they continued their reconnaissance to identify weak spots in the enemy’s defensive positions against which to conduct an attack. Their perseverance proved invaluable, as it led to intelligence that shaped Lee’s plan and ultimately decided the battle’s outcome.

Lastly, once the cavalry identified the weak spot and Lee developed the scheme of maneuver, the Confederates still continued to conduct reconnaissance. By commissioning Hotchkiss and a resident of Chancellorsville to conduct a route reconnaissance, Jackson was able to confirm the feasibility of his tentative scheme of maneuver to flank the enemy. The Army of Northern Virginia’s adherence to the fundamental of continuous reconnaissance throughout the Battle of Chancellorsville allowed it to successfully understand the enemy’s course of action and react to regain the initiative.

The Confederate cavalry’s success at Chancellorsville was also based on its retention of freedom of maneuver throughout the campaign. Retaining freedom of maneuver means to maintain battlefield mobility by not becoming decisively engaged with the enemy, at which point reconnaissance stops and the fight to survive begins.37 Chambliss’ men retained freedom of maneuver by fighting small elements of the Union Army, then displacing. Had they not done this, they would have likely met certain defeat against an enemy more than six times their size. By not becoming decisively engaged, yet still continuing to fight for information, the scouts were able to further develop the situation by capturing men from different corps of the Army of the Potomac. This helped the Confederate leadership understand just how many units Hooker had sent toward their western flank.

Their retention of freedom of maneuver also allowed Stuart’s troopers to covertly identify the weakest point in the enemy’s defense. Undoubtedly, the scouts had to reconnoiter multiple points across the breadth of the Union army’s front. Maintaining battlefield mobility enabled them to accomplish this without being destroyed and costing Lee his greatest asset of the battle.

Stuart’s men also assisted other elements in retaining freedom of maneuver. Lee understood that for Jackson’s flank attack to be successful, his forces had to be able to move undetected to the enemy’s western flank. Therefore, he ordered the cavalry to cover their enveloping march. This cover by the Confederate mounted forces allowed Jackson to retain freedom of maneuver and preserve combat power by not becoming prematurely decisively engaged with the enemy, resulting in achieving complete surprise on the men of Hooker’s XI Corps.

Had the Confederate scouts not provided early and accurate warning, their continuous reconnaissance and retention of freedom of maneuver could have all been for nothing. This historical account is filled with examples of the Confederate cavalry providing early and accurate warning to Lee. Providing early and accurate warning is accomplished by detecting the enemy quickly and reporting accurate information to the main-body commander.38 Lee was able to determine Hooker’s intention of flanking the Confederates from the left because of the reports he was receiving from his scouts early in the campaign. Lee received these reports early enough to issue Special Orders No. 121 to redirect his forces and prevent an enemy envelopment of their positions. The course of the battle over the next several days proved the accuracy of the reports as well.

The cavalry again demonstrated its proficiency with providing early and accurate warning on the evening of May 1, when Stuart informed Lee of the enemy’s weak western flank. Despite having to be sent through multiple echelons of command before reaching Stuart and, ultimately, Lee, the reports arrived in time for Lee to send Jackson on his famous 15-mile march around the Union army’s western flank. Rodes, Jackson’s lead division commander, soon found out the accuracy of the reports as he was able to roll up the entire Army of the Potomac from its right flank and send it fleeing back across the Rappahannock. The ability of junior scouts to communicate effectively by recognizing and prioritizing what information was important for higher commanders to make a decision and then ensuring it was delivered in time for decisions to be made and orders issued was paramount to the Confederates’ success.

Perhaps the best summation of the role the Confederate cavalry played at Chancellorsville was written by Union MG John Dix in a telegram to Peck May 1, 1863, in which he concluded, “Among the many marvels of this war are the impossibility on our own part of getting information as to the enemy and the facility with which he ascertains everything as to us.”39 Seeing the important role the cavalry played at Chancellorsville, Lee wrote a note to Davis May 7 asserting that “unless we can increase the cavalry attached to this army, we shall constantly be subject to aggressive expeditions of the enemy. ...”40 The Confederate cavalry demonstrated its immeasurable value through its application of reconnaissance and security fundamentals, allowing the Army of Northern Virginia to win one of the most famous upsets in history and set the conditions for the most iconic battle of the Civil War: Gettysburg.

The Confederate account at Chancellorsville highlights the significance of conducting reconnaissance and security operations. It demonstrates the paramount importance of conducting reconnaissance as a prelude to offensive operations to allow commanders to “see first, understand first, act first and finish decisively.”41 Reconnaissance, conducted by specifically trained and organized forces, empowered by the exercise of mission command, is just as important on modern battlefields as it was at Chancellorsville in 1863. While aviation, indirect fires and surveillance technology complement reconnaissance capabilities today, digital sensors cannot replace an individual Soldier’s ability to adapt to rapidly changing situations on the ground and fight for information to understand the enemy’s intent. Without such reconnaissance, commanders fall prey to an overreliance on conducting movements-to-contact instead of using cavalry to disrupt the enemy’s decision-making cycle and shape the battlefield to fight under more favorable conditions.

Furthermore, this account exemplifies the significance of preserving combat power through security operations conducted by units other than the main-body protected force. If commanders do not have designated security elements, they must decide to either forgo security operations entirely or divert combat power from the main body to protect the rest of the force, thus affecting their ability to mass the effects of combat power and finish decisively. Security operations enable the attainment of other operational fundamentals by the protected force – such as the fundamentals of the offense at Chancellorsville. Using the cavalry to cover Jackson’s move to the enemy’s flank enabled him to surprise the enemy from the west. Also, providing flank security during Jackson’s assault allowed him to concentrate the effects of his forces on the enemy’s weak flank and maintain a rapid tempo. Planning for security operations, conducted by formations trained and equipped to conduct them, can pay huge dividends for the main body at the decisive point of an operation.

The Battle of Chancellorsville provides insights into the timeless dynamic nature of reconnaissance and security operations. As Lee had in the veteran scouts under Stuart’s leadership, cavalry operations require tactical specialists specifically trained, equipped, experienced and organized to provide reconnaissance and security capabilities to the commander. This cannot be accomplished by simply assigning a tactical enabling task to any maneuver unit in the formation. Chancellorsville, among other Civil War battles, was extremely symmetrical for the senior commanders. Officers from each side went to the same schools and understood the same doctrine. Soldier training was the same. The formations used were the same. Each army was organized the same. The primary variable that allowed the Confederates to outmaneuver their numerically superior enemy was their adaptation and use of reconnaissance and security elements to develop the situation.

Uncertainty about the enemy cannot be eliminated through analysis (intelligence preparation of the battlefield) and detailed planning alone. Leaders must be able to adapt to changing conditions during execution, united by a common purpose and understanding of enemy capabilities. Although today’s battlefields may not call for large cavalry formations as they did during the Civil War due to technological advances in communication, mobility and firepower, they do call for mentally agile leaders capable of adapting tactical fundamentals to rapidly changing situations against a competitive enemy.

Notes

1 Blakeman, A. Noel, ed., Personal Recollections of the War of Rebellion: Addresses Delivered Before the Commandery of the State of New York, Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States, No. 2, New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1897.

2 The War of Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, Ser. 1, 25 (2), Washington: Government Printing Office, 1880-1901; book on-line at http://cdl.library.cornell.edu/moa/browse.monographs/waro.html, accessed Jan. 20, 2014; hereafter cited as OR.

3 Smith, Carl, Chancellorsville 1863: Jackson’s Lightning Strike, Oxford: Osprey Publishing, 1998.

4 Ibid.

5 Ibid.

6 Ibid.

7 Furgurson, Ernest B., Chancellorsville 1863: The Souls of the Brave, New York: Vintage Books, 1992.

8 Hamlin, Augustus Choate, The Battle of Chancellorsville, Bangor: Augustus Choate Hamlin, 1896.

9 Ibid.

10 Ibid.

11 Long, A.L., Memoirs of Robert E. Lee: His Military and Personal History, New York: J.M. Stoddart & Company, 1887.

12 Furgurson.

13 OR.

14 Long.

15 Longacre, Edward G., Lee’s Cavalrymen: A History of the Mounted Forces of the Army of Northern Virginia, 1861-1865, Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2012.

16 OR.

17 Long.

18 Furgurson.

19 Ibid.

20 Ibid.

21 Ibid.

22 Ibid.

23 Martin, David G., The Chancellorsville Campaign: March-May 1863, Conshohocken: Combined Books, Inc., 1991.

24 Long.

25 Ibid.

26 Smith.

27 Ibid.

28 Ibid.

29 Ibid.

30 Ibid.

31 Cullen, Joseph P., The Battle of Chancellorsville, Harrisburg: Easter Acorn Press, 1968.

32 Ibid.

33 Smith.

34 Cullen.

35 ADRP 3-90, Offense and Defense, Washington, DC: Headquarters, Department of the Army, 2012.

36 Army Techniques and Procedures 3-20.98, Reconnaissance Platoon, Washington, DC: Headquarters, Department of the Army, 2013.

37 Ibid.

38 Ibid.

39 OR.

40 Ibid.

41 Rosenberger, John D., “Breaking the Saber: The Subtle Demise of Cavalry in the Future Force,” Association of the United States Army Landpower Essay Series No. 04-1, The Institute of Land Warfare, 2004.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook email

email print

print