Knowledge Management at the Brigade

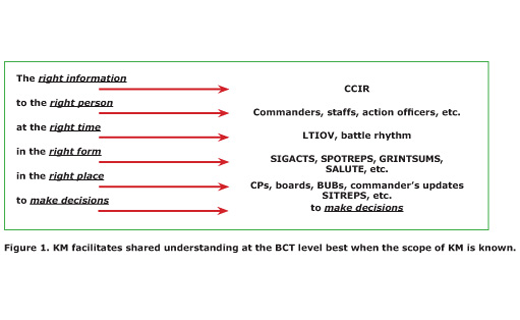

Knowledge management (KM) exists as a process for facilitating more effective mission command. Realistically, our units can increase their effectiveness by applying a systematic view of KM at the brigade level. By educating the correct personnel; reviewing the process by which information is shared; adjusting how our infrastructure or units are organized; and adapting which tools we use to actively see ourselves and off which we fight, our brigades can continue to build efficiencies and make our commanders’ ability to execute mission command effective.

Recognizing that KM exists as a process for facilitating more effective mission command has been a slow revelation for many of our formations. Most brigades acknowledge this need, and some even post banners in their tactical operations centers (TOCs) that read, “Who else needs to know?” Unfortunately, most units have not identified a systematic method for getting knowledge to those other units “who need to know,” whatever it is that needs to be conveyed.

The KM process, as per Field Manual 6-01.1, focuses on identifying knowledge-sharing gaps in four areas: procedures, personnel, tools and organization. While this methodology is vigorously applied at division-level organizations or higher, in brigades KM is often employed as an afterthought or with a very limited conscious scope.

During recent direct-action rotations at the National Training Center (NTC), units have had their KM officers (KMOs) focus almost exclusively on portal management. Though this is a critical element of KM, it really only addresses the tools aspect of sharing information – and ultimately knowledge – with subordinate battalions, companies and platoons. By not addressing all aspects of the KM methodology, brigades have lost much efficiency during their missions. Therefore the purpose of this article is to identify shortcoming trends as they relate to the four focus areas of the KM methodology: people, process, tools and organization.

People

Acknowledging that everyone executes KM to some degree, it is surprising that the KMO’s role often relegates to an additional duty. It is most useful to employ a dedicated staff agent to actively look for knowledge-sharing gaps rather than trust to intuition from throughout the staff as a whole. Making the application of KM should be the KMO’s dedicated mission. The KMO’s capacity to effectively identify gaps and offer solutions often increases if he or she has attended the KM course.

The KMO position at the brigade combat team (BCT) is a 53- (systems automation) or 57-series (simulations operations) major. Regrettably, this billet goes unfilled because of the limited number of officers in these functional areas. It is unrealistic to expect, with the demands for these functional areas at higher echelons, that we will have greater fielding of these positions in the future. Only one out of the four recent Army combat training center (CTC) rotations was filled with the appropriate 57-series officer. This is why most often the KMO is designated as an additional duty. This is acceptable, and in some cases may even be more useful, at brigade level.

Officers identified for the additional duty of KMO generally focus on their primary position. This is most vivid when the additional duty is placed on the S-6 or one of the S-6’s personnel. This provides adequate attention on the BCT’s portal but does not address other aspects of BCT KM vigorously – or, in some cases, at all. Ironically, KM is being applied by most members of the staff at all times, but the lack of centralized review of all warfighting functions (WfFs) as applied to a mission leaves operations disjointed when they transition from the planning phase to execution.

The critical member for this centralized clearing is the brigade executive officer. The KMO can facilitate the executive officer’s ability to synchronize efforts throughout the staff by identifying gaps for him that he may have not noticed. One brigade in particular assigned the additional duty of KMO to one of their battle captains. As this officer had constant exposure to all WfFs and sought speedy updates and transfer of orders and data to subordinates, he was able to quickly inform the executive officer. This helped the executive officer leverage his position so he could contact subordinate battalions or even brigade staff agencies to close knowledge-sharing gaps.

We believe that had the battle captain attended the Army Knowledge Management Qualification Course, his utility in identifying gaps in knowledge sharing within the brigade would have been even more valuable.

Process

Not surprisingly, the military decision-making process (MDMP) is adequately understood by our formations at the brigade and lower staffs, as there is a great deal of training and common understanding for the process. Unfortunately, the transition from mission orders to execution is often clumsy and disjointed. Frequently this is due to the executors in the staff not being at rehearsals or understanding the process that developed certain products like the wargame. The most vivid example of inconsistent process is rehearsals. The KMO has rarely been involved in this process for any rotation yet, and this is perhaps the most useful mechanism for gaining shared knowledge with subordinate units.

Brigades execute rehearsals consistently. However, the effectiveness of these rehearsals is often so limited that the synchronization and understanding one would gain from them is lost. Simple review of location, travel time for subordinates, rehearsal format, agenda and noise level all can make the process for executing the rehearsal (whether Central Army Registry (CAR), fires, sustainment, etc.). The trend has been that the planner or operations officer (S-3) assumes this responsibility exclusively.

When the timeline is condensed, the rehearsal’s presentation can become very distracting. This is most vivid when many company commanders are crowded about a very small map they cannot see, nor can they hear the speaker addressing them. Using the KMO as the notetaker at a minimum would force him into a position where he could review possible knowledge-sharing gaps. His involvement in set-up would also help identify needless distracters.

Another area where the KMO can apply great value is in working with the commander, executive officer and operations officer in developing a battle rhythm. This is a critical task for KMOs at division-level headquarters. At the brigade, however, the executive officer or S-3 – or sometimes even their subordinates – usually build the timeline and battle rhythm. Though it is not necessary to employ the KMO in this process, it is valuable if one is trying to identify avoidable future gaps.

The most successful brigades have incorporated into their battle rhythms not only their higher headquarters’ events but also their subordinate task forces’ timelines. By incorporating these timeline events (including key MDMP events), the battle rhythm becomes a tool the planners and the current operations (CUOPS) personnel can use. The process for reviewing the battle rhythm is the element, which is most inconsistent among the brigades who have passed through the NTC. The brigade who had the most valuable battle rhythm had a systematic process for its review, which occurred daily and was adjustable.

Most importantly, the review of the battle rhythm helped the planners avoid disrupting battalion timelines. This process of reviewing the battle rhythm, compounded with useful application of rehearsals, alone created advantages for brigades by facilitating mission command and making units more efficient.

Tools

Given the people and processes applied already at the BCT, these efforts are strengthened through use of effective tools. Many of these tools are constructed during the planning phase and are later refined during rehearsals. All these tools articulate what is most important to their commander’s ability to leverage mission command. Furthermore, these tools are a useful way for the commander to focus his staff and subordinate commanders.

While every BCT staff generally constructs running estimates, maps, communications equipment, decision-support matrixes (DSM), execution matrixes, preformatted conditions and checklists, they are inconsistently used. Sometimes brigades fail to use their own tools in the same fashion in a span of hours!

The two areas that have facilitated the commander’s ability to make decisions are running estimates and DSMs.

The DSM has enabled brigade and battalion commanders to fight their battles under constrained communications conditions. It is often unrealized that the DSM also helps staffs to quickly make recommendations to their commander and prepare for follow-on events as they relate to everything from sustainment to fires. One brigade in particular was able to maintain momentum during the fight after having lost direct communications with their commander by using their DSM in the tactical operations center (TOC). This helped with vehicle recovery, casualty evacuation and resupply. The command team emphasized this tool at the CAR so it was clear that this was important to the commander, so all the task forces and the BCT staff knew what their commander needed.

However, the trend is not as positive for most units. The norm is that brigades construct a useful DSM that is neither viewed nor understood by all agencies in the TOC or tactical command post (TAC). The degree of surprise when a critical event occurs that is related to a decision point is not, in most cases, a measure of lazy or disinterested staff members. Rather, there is a lack of understanding of how this tool is used. It compounds when staff agencies are not present at rehearsals or cannot understand the plan.

Running estimates also facilitate not only a more speedy application of the MDMP but, just as importantly, help in maintaining a accurate picture of the brigade during CUOPS to paint an accurate picture for the commander. If used well, the running estimates also share this information and knowledge with subordinate agencies and task forces. KM applied to showing our running estimates is an essential component of building a practical and useful common operating picture (COP). Running estimates for many brigades are often bland quad charts, which are very unwieldy and impractical for conveying knowledge quickly.

The most practical tool brigades use at the NTC are formatted to the type of information WfFs desire to convey, as well as having a process through which updated data is identified and captured quickly – like consumption reports over the Battle Command Sustainment Support System, or combat slants submitted over Jabber and Force XXI Battle Command Brigade-and-Below (FBCB2). The least successful tools – and unfortunately the trend – are running estimates that exist on a staff agency’s laptop but are never referenced anywhere or updated in the main command post.

This was mostly visible with one brigade where the staff did not have accurate running estimates for any WfF. The brigade commander felt far more comfortable excluding the staff completely because he had little faith in them.

To mitigate the trend of poor and not-useful running estimates, the KMO is useful as the briefer of these tools at battle-update briefs or even commanders’ update briefs. This would allow the KMO to interact with the commander, executive officer, S-3 and subordinate commanders to ensure receipt and distribution of the knowledge the commander seeks.

Organization

Efficiency is also built by the adjustment of our organization within the brigade. Normally, this is viewed as a method for addressing task organization. The most common KM-specific adjustment to our task organization is the movement of retransmission elements, depending on what nets the brigade desires to transmit and adjusts according to the transitions brigades anticipate during their fight (like movement-to-contact into the defense).

The trend, though, is that the retransmission nodes are forgotten until later in the MDMP so that transitions become sloppy. This adversely affects communications and forces commanders to resort to other methods on their primary, alternate, contingency and emergency communications plan, as well as the other warfighting functions when passing reports.

However, task organization is just one aspect where KM can increase efficiency. The actual layout of some of our facilities in some cases provides for incredible increase in effectiveness for sharing knowledge. One vivid positive example of this deliberate reorganization of structure relates to one rotation’s BCT main command post.

Every BCT maintains an analogue mapboard in the main command post on which their battle captains, executive officers and commander fight from and track when not focusing on the digital COP. Sadly, this map is generally an afterthought and lacks utility other than as a failsafe. It is most often ignored.

This was not the case with one BCT, which chose to place the map in the middle of the main command post floor in front of the digital displays but behind the battle captains’ row. This initially seemed awkward but turned out to provide much better situational awareness for all staff agencies. The executive officer who fought off the analogue map could look up to get confirmation from the FBCB2 feed as well as other running-estimate displays. The staff was arrayed around the map so all WfFs were involved, so they were able to quickly offer recommendations to their commander.

With the TOC’s arrangement and KMO’s presence, the reconciliation of the pictures the TAC and TOC see may be addressed more easily.

Realistically, our units can increase their effectiveness by applying a systematic view of KM at brigade level. By educating the correct personnel; reviewing the process by which information is shared; adjusting how our infrastructure or units are organized; and adapting which tools we use to actively see ourselves and off which we fight, our brigades can continue to build efficiencies and make our commanders’ ability to execute mission command effective.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook email

email print

print