Too Light to Fight: the Infantry Brigade Combat Team Cavalry Troop In Combined-Arms Maneuver

The Army's cavalry units are beginning to rehone their fundamentals and core competencies in the absence of organizational memory. Commanders, staffs and junior leaders in reconnaissance organizations must relearn forgotten skills. Unfortunately, it is not enough to simply relearn the skills and techniques that have faded from organizational memory to ensure future battlefield success; too much has changed in the past decade. During the past 10 years, as the Army has been fighting low-intensity wars, its structure, and therefore its concept of warfare, also changed. Unfortunately, these concepts are rooted in dangerously faulty assumptions that ignore previous decades of combat-proven methods in the name of wishful thinking and doctrinal catchphrases.

The purpose of this article is threefold. The first is to highlight some of the potentially fatal drawbacks of the infantry brigade combat team (IBCT) force structure. It is very easy for leaders who have spent their entire careers in light formations to look at uparmored humvees fitted with Mk-19s, .50-caliber machineguns and tube-launched, optically tracked, wire-guided (TOW) missiles and see a powerful maneuver formation. The reality is that in combined-arms maneuver (CAM), IBCT cavalry troops are glass cannons; for all their firepower, they can be quickly annihilated by a single boyevaya mashina pekhoty (BMP), bronetransportyor (BTR) or even boyevaya razvedyvatelnaya dozornaya mashina (BRDM-2). Failure to recognize this and to task the cavalry troops accordingly is tantamount to condemning the scouts to a death sentence.

The second purpose of this article is to share experiences so that other units can incorporate the tactics, techniques and procedures (TTPs) gleaned in training before they learn them the hard way in the crucible of war. The fundamentals and TTPs used here apply to the armored and Stryker BCTs (SBCT) counterparts with potentially greater effect.1

Third and finally, this article is intended to generate meaningful discussion within our community. Readers may walk away from it and insist that the IBCT cavalry squadron really is just fine the way it is. Or, they will walk away angry and demand some substantive changes to the IBCT cavalry squadrons.

Problem statement

One of the more challenging maneuvers the pre-war-on-terrorism Army fought hard to maintain proficiency in was the defile drill. Once upon a time, this CAM was conducted by reinforced mechanized brigades, brimming with armor, engineer, howitzer and aviation support. The Army looks different now, and IBCTs and SBCTs may find themselves assuming these missions. The enemy, still lethal, is now expected to prioritize asymmetric warfare, with the enemy heavy artillery replaced by mortars and the armor replaced by armored cars and technical trucks.

Despite these changes, real or perceived, some of the missions will not change. There will still be enemies to fight, and there will still be canalizing terrain they will choose to make their stands. In IBCTs, the likelihood that these canalized "kill zones" will first be encountered by cavalrymen operating deep in sector and alone is high. But cavalry squadrons lack the infantry battalions' ability to sustain combat and absorb casualties. Where breaches are concerned, scouts traditionally shaped the breaching tenet of intelligence. The breaching fundamentals (suppress, obscure, secure, reduce and assault) – the breach's actual execution – were never intended to be executed by scouts, and infantry only did so with the support of enablers and force multipliers. Unfortunately, many uninformed leaders see the cavalry troop as a powerful and survivable maneuver element. These leaders will mistakenly send the cavalry out to breach defiles without reinforcement.

This is the position in which 5th Squadron, 73rd Cavalry Regiment, from 3rd BCT, 82nd Airborne Division, found itself in October 2010 during the Joint Readiness Training Center's (JRTC) first CAM rotation in nearly 10 years. The previous decade’s rotations involved a period of pre-rotational training, followed by platoon-level situational-training exercises (STX) and culminating in a seven-day-long counterinsurgency (COIN) simulation. The October 2010 rotation was more reflective of the Cold War and 1990s, where company STX replaced platoon STX and the COIN simulation became a seven-day-long force-on-force (FoF) battle against a conventional opponent. The FoF exercise consisted of a four-day defensive phase and a three-day offensive phase where the BCT was to retake terrain held by a rogue mechanized infantry battalion. This exercise was discussed in the article "IBCT's Reconnaissance Squadron in Full-Spectrum Operations" (ARMOR, March-April 2011 edition), which also addressed strengths and other shortcomings of the IBCT cavalry squadron.

Alpha Troop (“Shadow Troop”) of 5-73 Cav was tasked with conducting a route reconnaissance along the southern axis of advance (Six-Mile Creek Road) to identify enemy positions and obstacles prior to movement of the BCT main effort. Though the mission was termed a "route reconnaissance," it was probably envisioned as a movement-to-contact. Six-Mile Creek Road is a hardball more than 12 kilometers long, lined with wooded, canalizing terrain along its entirety. The route is intersected by low-water crossings at four locations; even during the dry conditions of October, these water crossings were impossible to bypass except on foot; abandoning the troop's uparmored humvees after crossing the line of departure was not an option. These low-water crossings became textbook defiles. The enemy, recognizing this, established strong defensive positions with infantry, Infantry Fighting Vehicles (simulated BMPs) and tanks (simulated T-80s) defending each crossing.

Shadow Troop had serious shortcomings to deal with to accomplish the mission. First, the modified table of organization and equipment (MTOE) in effect predated the "R" series, allocating each scout platoon six trucks with only three-man crews; even with 100 percent manning, extended dismounted operations were impractical. Proposed MTOE changes plan on doubling the platoon's size from 18 scouts to 36 scouts and increasing the number of vehicles to nine. This overdue change allows a full-strength platoon to generate three dismounted teams, but an understrength platoon will still grapple with balancing dismounts against the personnel needed to effectively crew a humvee, particularly in the headquarters section.2 Progress has been made, but as long as scouts remain shackled to the corpse that is the humvee, generating dismounted patrols will be a problem.3

Second, the lack of long-range voice communications meant the troop command post (CP) also hosted a squadron retransmission element.4 This – combined with the troop mortar section’s need to minimize movement to provide continuous rapid indirect-fire coverage and the inability of the troop CP to defend itself (with the exception of the commander’s truck as the only gun truck and crew-served weapon in the headquarters, which is yet another MTOE shortcoming) – served to immobilize the troop CP for extended periods of time. Movement of headquarters assets, to include the first sergeant’s truck in support of casualty evacuation (casevac), became an operation more akin to jumping a squadron tactical CP than a simple troop CP move.

Finally, no engineer assets were available. An explosive ordinance disposal (EOD) team was attached to the troop, but leaders at all levels must understand that EOD teams are specialized to reduce improvised explosive devices (IEDs) only; EOD teams cannot pull "double duty" and reduce minefields. This is not only fallacy but also demonstrative of an inability to adapt from COIN. The mission’s context was high-intensity combat, yet many leaders remained fixated on COIN practices learned during Operation Iraqi Freedom, evident by allocating the EOD team.

What Troop A, 5-73 had was an abundance of fire support. A battery from 1-319 Field Artillery was allocated in direct support to A/5-73; instead of holding this battery at squadron level, the squadron commander wisely pushed this asset directly to the troop fire-support officer (FSO). The BCT had a task force of Army rotary-wing reconnaissance and attack aircraft attached to it; like the artillery support, the squadron commander pushed coordination with the aircraft directly to the troop FSO whenever they were made available to the squadron. After some trial and error, A/5-73 accomplished its route reconnaissance, reached its reconnaissance objective and developed effective TTPs in the process.

Proper conceptualization is necessary to successfully accomplish this mission. Instead of thinking of scouts as "maneuver elements," consider them as mobile observation posts (OPs) that incrementally move forward while smothering the axis of advance with indirect fires. To have any hope of survival, 100 percent of the enemy’s armored vehicles must be destroyed; a single BMP, BTR or even BRDM left intact behind the forward-line-of-own-troops spells mission failure and unacceptable casualties. This is not illustrative of "net-centric" warfare or sensor superiority, but it is reality given the limitations of force structure and equipment. It is also a way of balancing mission accomplishment with minimizing casualties.

Step 1: planning

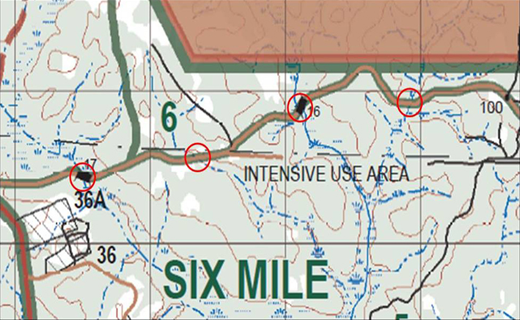

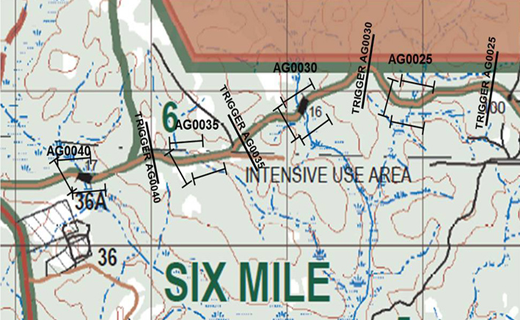

Intelligence preparation of the battlefield. The first step is to identify canalizing terrain that intersects the route of march: waterways or swamps; cuts in mountains or ridgelines; bridges; ravines, cliffs or canyons. Any place where the ability of vehicles to move off-road is hampered should be identified as a defile. This example refers to the water crossings circled in Figure 1.

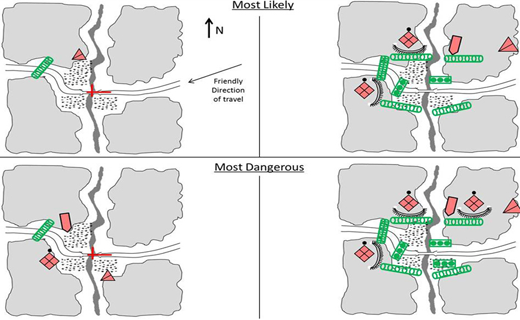

Enemy assets and the doctrinal template are considered with the location of the defiles. Defensive positions in the enemy’s security zone are there to identify, disrupt and "attrit" friendly forces before they reach the main battle area (MBA). If the position is in the MBA, the enemy’s objective is to destroy, and the defile serves to contain friendly forces in the kill zone. Depending on the enemy and terrain, there are likely to be similarities in the enemy’s deployment not only between the most likely and most dangerous courses of action (MLCoA and MDCoA, respectively), but also between the security zone and MBA positions (Figure 2). These similarities expedite fires planning.

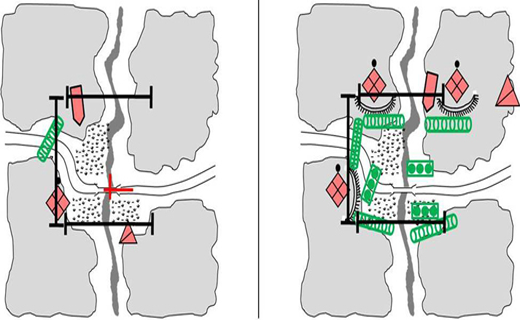

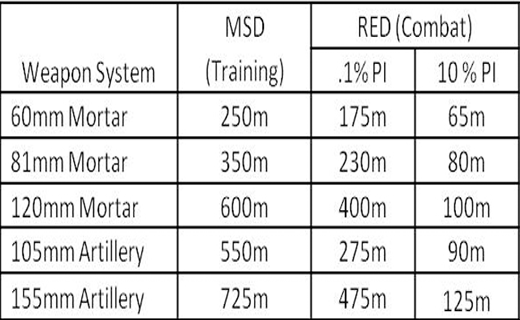

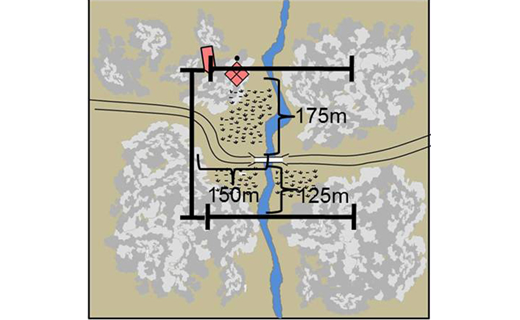

Fires planning. An examination of the enemy dispositions in Figure 2 should begin to conjure a specific pattern that would be able to have effects on the enemy regardless of whether or not their defenses are on the north or south side of the route – the pattern is a U shape. By creating a group of linear indirect-fire targets arrayed in a U, variations in the enemy deployment can be addressed (Figure 3). When plotting this group, the available fire support and its minimum safe distance (MSD) and risk-estimate distance (RED) for 10 percent and .1 percent of incapacitation (PI) are used.5 MSDs and REDs for common assets are listed in Figure 4. Since this can vary, a general rule is to plot the group no closer than 125 meters from the chokepoint (Figure 5).

The result of this, when applied to the whole route, will be a large number of fire-support targets. There are two good reasons for the large number of targets. First, targets are resource placeholders, a concept that is not widely understood. These placeholders should help the fires battalion and brigade FSO to allocate resources. Second, time is a luxury scouts rarely have, and artillery is dramatically more responsive when it is fired for effect at a preplanned group – or even shifting from a known point – when compared to adjusting fires against a target of opportunity. An extra five minutes spent planning can literally save tens of minutes during execution.6

The trigger lines to initiate fires need to take into account the terrain as well as the time delay between the call-for-fire transmission and the impact of rounds. A planning shortcut is to place triggers outside small-arms range or near a major terrain feature away from the target area (Figure 6). This allows the scout platoon to initiate the fire mission from cover. Proximity to the target group may require the trigger to be outside visual range of the target group, particularly if the nearest terrain feature is within MSD or RED range. Ideally, triggers should be placed so that by the time a dismounted scout reaches the .1 percent PI RED, the rounds should be just starting to splash on target.

Organization. Platoons may need to be reorganized for the troop to be effective. Gun trucks may need to be garaged at the squadron maintenance collection point to maximize the amount of scouts available for dismounted operations. Commanders need to carefully consider which trucks are left behind, taking into account maintenance status and weapon-system composition. At squadron level, any trucks deemed excess to mission requirements must be viewed as an asset that can be diverted to support the dismounted troop or to tactical-operations center (TOC) security.7

For a single avenue of approach, several formations are viable. If the terrain and enemy situation is permissible, tasking one platoon per route may be enough combat power to get the job done. In cases where there is a stronger enemy presence, spreading forces so thinly is a recipe for failure; multiple platoons may have to work along the same route, which introduces organizational challenges based on the reconnaissance focus and tempo. If speed is a priority, a V formation is effective.8 If engineer assets are attached, the platoon in the rear secures attachments, allowing combat multipliers like engineers to be forward and responsive. The rear platoon is in a position to maneuver in support of either forward platoon in the event of contact. If one of the lead platoons encounters a position that allows overwatch of the route, it can establish overwatch while the trail platoon can move forward to assume the reconnaissance mission.

If speed is less important, a modified-column formation is effective.9 The lead platoon conducts its push-pull reconnaissance along the route such that each section covers one side of the route (dependent on mission, enemy, terrain and weather, troops and support available, time available and civil considerations). The following platoon is postured to assume this lead role in the event the lead platoon takes contact and needs to consolidate and reorganize, its dismounts become exhausted, or it has reached an excellent support-by-fire position. The trail platoon moves up to the follow-and-assume-support role, while the former lead platoon moves to the trail position to quickly rest and reorganize. The cycle continues for the rest of the mission. Fighter management is incorporated into the scheme of maneuver so the lead platoon is not forced to sacrifice its dismounted capability because of exhaustion or dehydration; forward momentum never ceases.

A fundamental of reconnaissance is to not keep reconnaissance assets in reserve.10 However, this tenet cannot be applied without consideration of the friendly and enemy situation. If only one scout platoon is assigned to a route and the enemy is defending in force with any armor along that route, that platoon will probably fail in its mission and be annihilated in the process. Not leaving assets in reserve really means to not leave any assets unused. Scouts in reserve are not unused; keeping a platoon in reserve provides offensive depth and mass to a formation that is prone to overextension and unable to absorb casualties.

Step 2: execution

Dismounts. Dismounts must always be in advance of the lead vehicles. In a movement-to-contact, contact should be made with the smallest element possible; this can’t be achieved if a vehicle takes point. Leading with dismounts also increases the likelihood of detecting IEDs. The humvees, back in a concealed position, provide support by fire and emergency extraction for the dismounts.

The dismounts should move as part of a buddy team with separation between the two dismounts. There’s no rule for separation distance, but at any given moment, each scout must be able to see the other. One scout needs to be able to see the route at all times, and at least one humvee (likely the gunner) from the section needs to be able to see at least one of the scouts to enable use of hand signals. Using the standard push-pull method, once the scouts get out of the humvee section’s line of sight, the humvee element contacts the dismounts’ hold position until the humvee can move forward, after which point the dismounts resume their movement. Likewise, if the dismounted scouts identify a good intervisibility line or other covered position, they will call the humvees forward to establish support by fire.

Trucks. The humvees serve as the IBCT cavalry platoon’s firepower, resupply points, command-and-control nodes and casevac platforms. Short counts should only be used if the duration between bounds is reasonably long; repeat and unnecessary shutoffs and startups increase the likelihood of drained batteries and a vehicle not starting when it is needed most. Roads should always be avoided because they provide no cover and they harbor mines and IEDs. When road or trail use is unavoidable, speeds should be minimal with the exception of during casevac. If a vehicle is moving fast enough to kick up a dust cloud, it is moving too fast for reconnaissance.

Uparmored humvees do not perform as well off-road. The armor weight, combined with broken terrain, results in more flat tires than units are accustomed to dealing with after a decade of urban COIN operations. Supply requirements for COIN and full-spectrum environments are not the same; as an example, during Shadow Troop’s JRTC rotation, the BCT deployed nearly 1,000 pieces of rolling stock to the FoF exercise, yet neglected to bring along spare tires. Though anecdotal, this illustrates a lingering COIN mindset. Squadron S-4s need to ensure a surplus of tires exists, particularly if the mounted troops are using uparmored humvees; tires are cheap, lives are not. Until the humvee is replaced with a better scout vehicle, flat tires will be an inconvenient reality.

Mortars. The troop mortar section should be monitoring the fires net for cues throughout the mission. As trigger lines are crossed and fire missions are called up, the mortar tubes should be pre-emptively laid onto the target groups the artillery engages. This expedites any immediate suppression missions that may be required at these likely enemy engagement areas.

The mortar location will necessarily be co-located near the troop headquarters. The mortar section does not have the manpower to secure its firing point while simultaneously laying tubes and hanging round. The mortar section depends on the security provided by the troop headquarters, particularly the commander’s gun truck and the FSO’s Knight armored vehicle. During any troop CP moves, the mortars must be the first element to be established and the last element to displace.

Actions at trigger lines. The dismounted scouts call for a fire mission upon meeting one of the following criteria: reaching the trigger line, or reaching a covered and concealed location that affords observation of the target group. If the target is out of sight, the humvees and dismounts continue to push-pull forward while the dismounts move closer to the target area, taking care to stay outside the MSD/.1 percent PI RED radius. If the trigger lines have been set correctly, the dismounts should arrive at a position at the edge of MSD/.1 percent PI RED just in time to observe rounds on the objective, or – if necessary – with enough time to spare to abort the fire mission before the guns fire. This level of precision can be achieved through training and a working relationship with supporting batteries.

If the target area is clear, or if the enemy has been destroyed, the humvees are called forward, attached engineers breach any obstacles and the troop continues mission. If the dismounts identify a large enemy force, the preferred CoA is to call for fire, break contact and attempt to find a bypass.

If the surviving enemy force is small, it is possible to destroy and break through them thanks to the planning that has already taken place. The dismounts in contact, visual or otherwise, become support-by-fire and immediately adjust indirect fire onto the enemy. If the guns are still laid on the target group, adjustments to the previous fire mission will be fast and artillery will be responsive. If the guns shifted support to another unit, troop mortars (since they are already laid on) are effective. The humvees should move up and use their crew-served weapons as a supplement to the suppression being provided by indirect fires, not as a substitute. The humvees should replace the dismounts as the support force and assume observation of indirect fires where possible, allowing the dismounts to finish clearing the objective.

Once suppression is achieved, the dismounts perform Battle Drill 1.11 The dismounts become the assault force and the humvees are the support-by-fire. The engineers move with the dismounts to breach as necessary on the objective. Once the dismounts complete their assault through the objective, the humvees assault through and complete clearance of the objective. As the dismounts finalize actions on the objective and move forward to link up with the humvees, a following platoon bounds forward and assumes the lead in reconnaissance, maintaining the troop’s operational tempo. A third platoon assists with actions on the objective or casevac as needed. The platoon that cleared the objective consolidates and reorganizes. The entire scenario repeats itself at the next trigger line.

Results

The challenges faced by the IBCT mounted troops and their platoons can be daunting, but they are not insurmountable. As with all operations, planning is the essential element; the preceding process, though it has many moving pieces, is simple enough that it can be rapidly planned. Successful execution depends on the effective application of fundamental scout skills, some of which may have atrophied since 2003. This is remedied by training the process like a battle drill: through repetition and focusing on simplicity and fundamentals.

The above-mentioned process ended up being successful for Troop A, 5-73 Cav. By the end of FoF, the troop had fought its way through most of a reinforced motorized infantry battalion and reached its reconnaissance objective. Real-world casualties are difficult to estimate based on the nature of the simulation; artillery effects depend on fire markers doing their jobs, vehicles may not have a functional Multiple Integrated Laser Engagement System (if installed at all), and trainer/mentor coverage and control varies radically. Troop A, 5-73 Cav, accounted for 95 dismounts, seven BMPs, one BRDM, two T-80s and three technical trucks killed or destroyed over the course of a 16-kilometer penetration through enemy territory. The troop’s success was pyrrhic; only the troop headquarters and one scout platoon’s worth of men and vehicles were intact.12 A lot was asked of the scouts, and being scouts, they delivered.

What this says about IBCT cavalry troop and squadron

The need for this conceptualization highlights many problems inherent to the IBCT in general and the mounted troop specifically. The IBCT has limited survivability, so its infantry and cavalry elements are as wedded to their artillery support as our infantry was during World War I. The longest-range direct-fire weapon system in the IBCT, the humvee-mounted TOW, is optimal for defense, yet our doctrine calls for offensive action.13 The IBCT must have fires superiority before it can begin to accomplish its mission; this is an assumption that is absolutely critical, yet it rarely gets noticed during the military decision-making process if it gets noticed at all.

The batteries did not displace during the entire JRTC rotation; being towed howitzers, they lack the ability to self-displace after firing and to quickly re-establish themselves. This is why self-propelled howitzers were developed in the first place, and the IBCT has none. With our offensive doctrine, how does an IBCT guarantee fires superiority when its batteries can’t displace after firing? How will an IBCT fight when maneuver reaches the limits of artillery support, or if batteries are hit with enemy counter-battery fire, or if its radio network is jammed? The preceding example illustrates that such an event would paralyze the cavalry squadron.

The scout defile drill described is predicated on continuous and responsive fire support. A/5-73 required an entire battery in direct support to complete the mission with 30 percent of its manpower left intact. One battery may seem like enough to support a battalion, but considering the IBCT’s dependence on fire support, it is not. Realistically, one battery is needed for every two companies such that one firing platoon can directly support one line company. Before 2014, an IBCT had 11 maneuver companies (including the cavalry troops) supported by only two batteries; only 36 percent of the IBCT could receive an adequate level of fire support. Changes to the IBCT MTOE will soon result in 15 maneuver companies being supported by three batteries.14 This means 60 percent of the IBCT’s companies will receive dedicated fire support, and 40 percent (six companies) will not.

There is not enough artillery in the IBCT. The retort is that any lack in capability can be mitigated through the attachment of aviation and joint air assets, a retort that assumes and depends on unchallenged air supremacy. Since Vietnam, that assumption has usually been valid, but there is no guarantee it always will be. In the 2006 Lebanon War, Israeli ground forces had to use artillery to blast through countless Hezbollah defensive positions missed by air strikes. With the proliferation of man-portable surface-to-air missiles (SAMs), such as the 20,000 that went missing from Libya in 2011, attack aviation cannot sensibly loiter over the battlefield for long periods of time.15

Reality also conflicts with the "revolution in military affairs" where speed and mobility is concerned. Future operations are generally envisioned as rapid and fluid; exemplified by the 2003 invasion of Iraq, rapid and dispersed movement will serve to paralyze the enemy. However, cavalry-troop humvees capable of sustaining speeds of 55 miles per hour for 350 miles can only avoid detection by moving as fast as the 19-year-old scout with broken-in boots and an assault pack walking in front of the trucks; usually, this is one kilometer per hour. Due to the humvee’s survivability and the cavalry troop’s inability to absorb casualties, the IBCT’s "mobile" reconnaissance elements can only use 1 percent of their potential mobility.16 This is acceptable in certain circumstances, but only when this limitation is addressed in mission planning.

The weaknesses of the IBCT cavalry squadron should be apparent. The IBCT element with the most protection is vulnerable to man-portable light anti-tank weapons like the RPG-7. The loss of one dismount deprives a scout section of its dismounted capability; losing two dismounts renders the platoon non-mission-capable. The IBCT element with the most mobility is survivable when moving at the same speed as a dismount; the mounted cavalry troops are not much more mobile than the infantry battalions they are meant to support. The IBCT element with the most firepower can best employ its firepower in a defensive role, but screens do not employ direct fires and none of the cavalry squadrons can conduct guards.

It is futile to fight a mid- to high-intensity conflict with an organization optimized for low-intensity warfare. We expect the Army of the future to use sensors, precision firepower and measured violence against point targets. The JRTC exercise in question suggests that future warfare against a near-peer opponent would likely be a bloody grind and not a stealthy operation devoid of casualties. The IBCT cavalry troop has no "maneuver capability"; a cavalry trooper must act as a moving OP and employ rolling barrages akin to those used during World War I to survive. Quibbling over Ranger-coded billets within the cavalry troops is not going to produce meaningful improvement, nor will simply swapping the humvee out for a different vehicle. These organizations need substantive revisions.

The IBCT cavalry squadron is fundamentally flawed in many ways. The flaws are easy to identify; many revolve around vehicle platforms, some revolve around unrealistic expectations. It is not only in Armor Branch’s best interests, but also in the IBCT’s and Infantry Branch’s, to have a functional, practical and effective IBCT cavalry squadron. For cavalry and armor officers, who are the Army’s experts in mounted reconnaissance, the time has come to have an honest discussion of how to comprehensively fix this organization. If we wait until our nation faces a competent opponent that knows the business of war before we make changes, it will be too late. The time to fix the cavalry squadron is now.

Notes

1As a disclaimer, recognize that this method is merely "a way" for cavalry troops to conduct a defile breach hastily and "on the cheap." Ideally, engineer, infantry and armor would be attached to conduct a more deliberate defile breach. As such, this method assumes a high level of risk.

2Some cavalry and Army discussions, such as "One Size Fits All: the Future of the Scout Platoon and Squad" in the January-February 2013 issue of ARMOR, propose increasing the vehicle count to 10. However, this repeats the organizational problem the R-series MTOE had; 10 vehicles leave platoons with scout sections that can generate three dismounts each with no dismounts in the headquarters section, hardly ideal when the platoon leader needs to have his boots on the ground.

3The Army’s lack of a dedicated ground reconnaissance vehicle is discussed in more detail in “Ideas on Cavalry” in the October-December 2013 issue of ARMOR.

4High-frequency and tactical-satellite communications are not organic to the IBCT cavalry troop. Blue Force Tracker is required for communications beyond frequency-modulation voice range.

5One percent PI means one in 1,000 Soldiers could be incapacitated at the specified distance from impact. Ten percent PI means one in 10 could be incapacitated at that distance.

6See "So You Say You Want to Kill with Indirect Fires...," ARMOR, November-December 2002, and "Mortar Support in the Korean Defile," ARMOR, September-October 1997, for a more in-depth analysis and discussion.

7An uparmored humvee with crew-served weapons and radios can rapidly be used as strongpoint in the TOC security plan. This also reinforces the need to cross-train the Troop C scouts on humvees.

8This formation consists of two platoons forward, each covering a different side of the route, with one platoon in the rear to act as a reserve.

9In this case, "modified column" means having one platoon forward, a second platoon immediately behind in a follow-and-assume-support role and a third platoon further in the rear in as a rest or secondary follow-and-support element.

10See FM 3-20.98, Reconnaissance and Scout Platoon (2009), Paragraph 3-7.

11Platoon attack battle drill. As of 2007, battle drills have been removed from FM 3-21.8, though they are still referenced. They can still be found in FM 7-8, which is out of circulation but still referenced by 3-21.8 and still available on the Internet.

12Most casualties were sustained when the two lead platoons were halted, forced to move several kilometers backward over a previously cleared route and made to wait as a scatterable minefield was emplaced around them, cutting off all forward and rearward movement.

13The TOW on the humvee is an unstable platform. No TOW gunner can hope to acquire and hold missile guidance on even a stationary target while that humvee is moving over broken terrain.

14The 2x8 platoon and gun battery will become a 3x6 gun platoon and gun battery, resulting in more platoons with fewer guns.

15See Matt M. Matthews, "We Were Caught Unprepared: the 2006 Hezbollah-Israeli War," U.S. Army Combat Studies Institute Press, Fort Leavenworth, KS, Occasional Paper 26. Also see http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2011/09/27/nightmare-in-libya_n_983153.html regarding SAM proliferation.

16One percent is arrived at by dividing the dismounted rate of march (one kilometer per hour) by the humvee’s traveling rate of march of 55 miles per hour, or 88.5 kilometers per hour; 1/88.5 = 0.011, or 1.1 percent.

email

email print

print