The Bastogne Fusion Process: a Commander-Centric Approach to Planning and Decision-Making

“Commanders are the most important participants in the operations process. While staffs perform essential functions that amplify the effectiveness of operations, commanders drive the operations process through understanding, visualizing, describing, directing, leading and assessing operations.” –Army Doctrinal Reference Publication 5-0, The Operations Process, May 2012

In Spring 2012, as 1st Brigade (Bastogne), 101st Airborne Division (Air Assault), prepared to conduct collective training before deploying to Afghanistan, we determined the brigade staff needed to enhance our planning process to help gain a deeper understanding of the environment in a way that supported the brigade commander’s personality and way of thinking. The brigade commander was concerned that traditional methods and processes did not account for the Afghan environment’s complexity. How would the staff decide when and where to apply resources and effort?

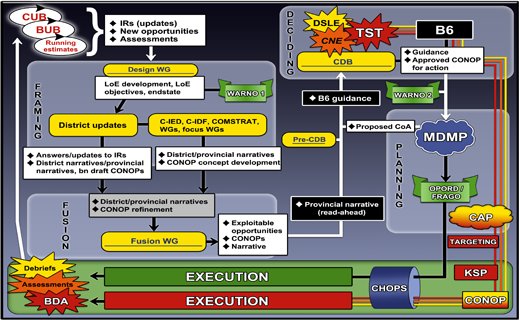

In an attempt to contribute to the brigade commander’s understanding of the environment, the brigade staff developed a commander-centric approach we called the Bastogne Fusion Process (BFP). The brigade applied this process while deployed to Afghanistan from November 2012 until August 2013 as a security-force assistance brigade.

This article’s purpose is ultimately to show how the brigade staff accounted for the commander’s personality in tailoring a planning and problem-solving process. In Afghanistan, where complexity and friction thrive at the crossroads of human and physical terrain, the staff validated the BFP and found it to be a sound approach to commander-centric planning and problem-solving built on a deep and accurate shared understanding of the operational environment.

Decision-making methods and processes

Although the Army operations process provides a template for planning and problem-solving with the Army design methodology and the military decision-making process (MDMP), a staff should tailor these processes with the commander’s personality in mind to maximize mission command and his/her ability to balance the art of command with the science of control. The correct inputs and outputs, synchronized within a process, should align with how a commander internalizes understanding and how his or her visualization of the environment reinforces his or her decision-making methodology. The process should also deepen the shared understanding of the operational environment (OE) across higher and subordinate commands to ensure the unit’s effort and resources are not applied against poorly defined problems.

BFP’s overarching goal is to provide feasible solutions to complex, ill-structured problems tailored to the commander’s thought process. Throughout the development and execution of this process, the brigade staff determined that BFP exhibits several characteristics:

- It is adaptable to fit the commander’s thought process and his or her decision-making horizons.

- In allocation of time, 75 percent is dedicated to preparation and 25 percent is dedicated to planning and execution.

- BFP accommodates short- and long-term problem sets.

- BFP is an iterative process that ensures actions are tied directly to a deep understanding of the environment.

- BFP focuses on uncovering opportunities.1

- It avoids offering simple answers to complex problems; simple approaches are easy to understand, but often ineffective in execution.

- BFP is resilient to friction and turbulence as friendly actions create new circumstances (intended and unintended) in the environment.

- BFP uses comprehensive inputs from subordinate commanders and staffs to frame the problem set.

- BFP changes conceptual thinking into executable orders; it finds the critical transition point between conceptual and detailed planning.

- Inputs are designed to be intuitive, easy to use and clearly understood down to the platoon. The BFP does not seek to replace design or the MDMP. Instead, it ensures that mission analysis is thorough and clarifies the problem set. Throughout many iterations of this process during the brigade’s Mission-Command Training Program (MCTP) – the brigade warfighter exercise, Joint Readiness Training Center (JRTC) rotation and deployment to Afghanistan – the staff continued to refine the BFP to improve the brigade’s understanding of the environment and its ability to describe it in a manner that resonated with the both the staff and the commander. This process also had to transform a conceptual plan into detailed executable orders for subordinate units and ensure that the action was being assessed appropriately to restart or continue the process with enough data points.

Defining inputs

The information that goes into any process – the inputs – must be carefully considered. One consideration used to determine relevant inputs was to ensure we were not creating redundant reporting requirements for subordinate commands and staffs. The brigade commander’s battle rhythm was used to identify those venues and existing reporting requirements as well as higher’s battle rhythm to avoid overloading a subordinate staff officer with redundant reports. (It is no secret that a brigade staff can quickly overwhelm a battalion/squadron staff with reporting requirements that do not serve as valid inputs to a relevant process.)

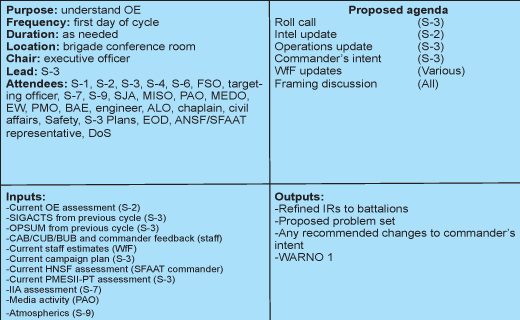

Once the standard reporting requirements were outlined, the staff identified efficiencies within those reports that would contribute to the brigade commander’s visualization of the environment. The battle rhythm consisted of Commander Update Briefs (CUBs), Battle Update Briefs (BUBs), warfighting function (WfF) working groups (WGs), staff updates and Commander Assessment Briefs (CABs) – all designed to serve as inputs to the BFP.

Finding the correct inputs was a continuously evolving process that assessed whether or not the information requested actually benefited the BFP. Getting rid of a report or staff estimate that did not make sense was occasionally a significant emotional event for staff officers who had adopted the processes from the previous staff or from a previous job. We determined that inputs and venues must be synchronized and sustainable. They should also contribute and be formatted to the brigade commander’s visualization to gain efficiency in staff work.

Also, understanding the impact a commander has on the OE while conducting deliberate/dynamic engagements and battlefield circulation is critical for the staff. Assembling the brigade staff with the commander following battlefield circulation is a technique the staff developed in Afghanistan. This meeting ensured staff situational awareness and prevented the development of divergent views of the OE. Initially, this meeting involved all brigade staff officers. However, with increasing requirements, only key or select staff officers were required for future meetings. In this case, the commander used his weekly staff update to provide insights to the remainder of the staff.

Framing the problem

One of the primary characteristics that made the BFP successful is the integrated staff approach that fostered an environment where all participants were encouraged to challenge the status quo and to question assumptions. The critical phase in the BFP, framing the problem, was the forum for such collaboration.

Initially, this series of meetings with the entire brigade staff was frustrating and often did not produce the outputs desired. When trying to define a complex problem set, it proved to be difficult to identify a start point. As a result of trial and error, the staff determined that identifying the right contributors, proper framework and an open mindset go a long way in making this key step successful.

In practice, the design WG is a room populated by whiteboards, with representatives from each staff section and interagency representatives. The rank of the participants was not considered as a prerequisite for contributing. Instead, new and unconventional approaches were welcome in a generally doctrine-laced environment of post-captain’s career course and Intermediate Level Education graduates. For example, we noted that enlisted intelligence analysts had a deep understanding of a specific topic, ethnic group or geographic location. Their perspectives were essential in developing a complete picture of the OE. In many cases, the non-combat-arms officer, chaplains and lawyers gave some of the best insights because they were able to widen the aperture and look at the OE through a different lens.

Meetings were also framed around a range of variables depending on the OE. For example, the operational variables – political, military, economic, social, information, infrastructure, physical environment and time (PMESII-PT) – worked to effectively describe an Afghan province or district. Strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats (SWOT) analysis was also used when attempting to describe a specific element such as the Afghan National Army (ANA) or a Taliban sub-commander in the area of operation.

The method used to capture this critical discussion is not paramount. Instead, a staff should use the framework that will resonate the most with how your commander thinks and how he/she sees his/her environment. For us, as conversations began to answer or describe the chosen variables, it became easier to identify the problem set and recognize opportunities that clearly involved multiple variables. Through this process, the staff modified the endstate initially drafted by the brigade commander.

It is important that the staff not approach this process strictly within their WfF, but more like a student who is asked to read a novel and then give his/her opinion and raw ideas – it should be an informal discussion where new ideas are accepted instead of in a canned briefing format. This approach enabled each staff member to draw from his/her background, education and experiences rather than focusing narrowly within his/her WfF. The staff also understood that challenging assumptions and thoughts was highly encouraged because it forced them to come to the meeting prepared to defend their positions.

These meetings were not one the commander would normally attend. On occasion, the commander would sit in the back of the room to gain insight on discussions and thought processes, but mostly he allowed the staff to continue to muddle through this phase and formally present the proposed problem set for approval.

Subordinate units played an important role in this phase as well. During the early stages of the framing phase, the brigade staff developed information requirements (IRs) based on gaps in knowledge of the environment. The staff would categorize these IRs along the same variables used to frame the problem (i.e., PMESII-PT or SWOT). Those IRs were immediately distributed to the battalions, and the brigade staff relied heavily on their feedback to help achieve a better understanding of the environment. Bringing in this bottom-up refinement early in the BFP was essential, as it helped validate thought processes and built credibility into the staff’s recommendations to the commander.

Fusion

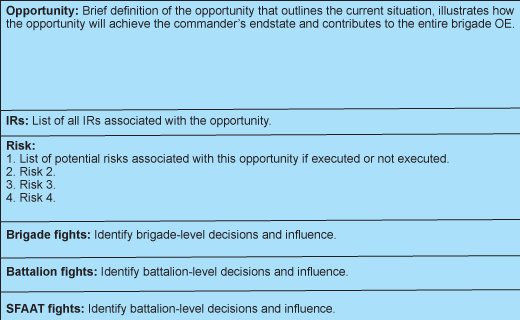

The next phase of the BFP is the process of “fusing” all the data garnered from the previous framing phase. The inputs into this fusion phase included subordinate feedback to the IRs, a proposed problem set, recommended changes to the commander’s endstate, proposed lines of effort (LoEs) and draft opportunities. Multiple opportunities were identified within each LoE. These opportunities provided operational orientation for the brigade’s efforts. It is through those opportunities for success that the brigade staff would apply the traditional MDMP resulting in a detailed order given to the subordinate units for action.

In the fusion phase, the staff refined the identified opportunities based on the staff’s understanding gained during the framing phase. In preparation for the commander’s review, the staff defined each opportunity in a written description of the current state of the environment that required this action and the action being proposed to respond to that state. Also defined was the risk associated with the opportunity if not executed or if executed ineffectively, as well as identifying who owns “the fight” at each level. This helped prioritize resources and establish unity of effort.

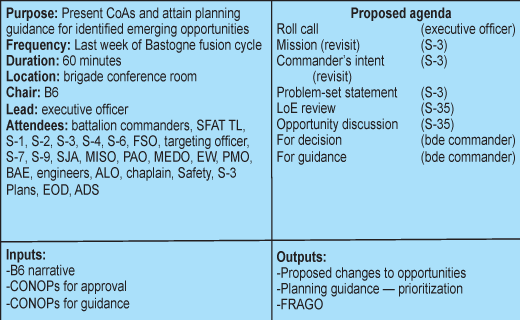

It is important to note that a full course-of-action (CoA) brief was not the target, but a one-slide description that explained the opportunity was. Figure 3 outlines this template. To prevent wasted effort, the staff would not conduct any more planning until the opportunity was approved and prioritized during the Commander’s Decision Brief (CDB).

The output of this phase was a written brigade narrative – not a PowerPoint presentation – that would be given to the brigade commander for review before seeking a decision from him. The combined brigade narrative included a narrative from each of the battalion commanders and one from the brigade staff. To prevent the brigade staff from regurgitating what the battalion commanders were saying in their narratives, a proposed problem set, defined LoEs and opportunities that met the criteria of cross-cutting multiple LoEs were presented in the narrative.

The embedded battalion commanders’ narrative was the forum for subordinate commanders to articulate to the brigade the current state of their OE and any emerging opportunities and exploitable networks (friendly, enemy or mutually supporting). It was through this narrative format that the brigade commander could best internalize the information. This narrative would also act as the read-ahead before our CDB in the following phase.

Deciding

Pinning down the commander in a combat environment for a decision is nearly impossible when he or she has not been given ample time to think. Creating a read-ahead narrative – the combined brigade narrative – and a desk-side huddle with the deputy commander, executive officer, S-3, S-2 and targeting officer prior to the formal decision brief was critical. This quick meeting helped the commander focus on what decisions were being asked of him and when the decision was needed.

The desk-side huddle also provided insight on where the brigade commander was leaning concerning prioritization and approval of the opportunities, which allowed the brigade staff to begin the initial steps of MDMP. It also provided insight on what opportunities were misaligned with the brigade commander’s read of the environment. This normally led to analysis on more opportunities not initially identified.

The brigade CDB was the final step before moving into the MDMP with each opportunity. This brief involved all battalion commanders and brigade staff officers. This forum was not for the weak of heart; the staff would defend their product to the brigade and battalion commanders so each fully understood the background and operational approach; transparency between brigade and battalion staffs was essential, and argumentative discourse was encouraged. The discourse that derived from this forum helped refine the brigade commander’s planning guidance and approval of our operational approach.

At the end of this meeting, the brigade staff would have prioritization on which opportunities to continue planning on and any adjustments to the problem set, LoEs or commander’s endstate.

Planning and execution

Once the commander decided where to prioritize his efforts and apply resources, the brigade staff used the remaining 25 percent of time to conduct the more traditional MDMP steps. Mission analysis focused on the tangible aspects of resourcing the actions inside the defined OE – facts, assumptions, tasks and limitations – instead of trying to understand stakeholders, networks and the human terrain. Most of the time was spent on CoA development.

The benefit of the BFP up to this point was that the battalions were read in on the opportunities and, in most cases, developed them in conjunction with the brigade staff. This allowed for several efficiencies, including parallel planning and the brigade staff’s ability to immediately request the enablers needed from the regional command headquarters.

Another benefit that inherently emerged from this process was that everyone on the brigade staff understood the intellectual underpinnings of the operation being planned and how it tied to the brigade’s campaign plan. The output of this phase was an executable order (fragmentary order (FRAGO), operations order (OPORD) or concept-of-the-operation (CONOP) order) directing subordinate units to take the necessary actions to achieve the commander’s endstate.

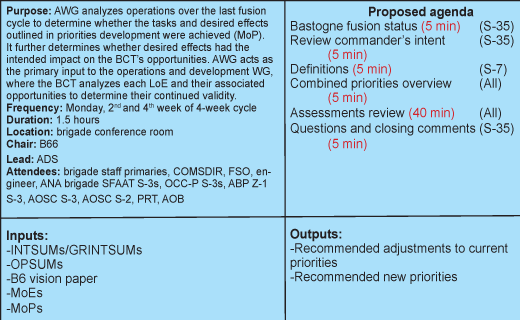

Assessing the effects of the operation always created friction points among the staffs based on the read they were getting from the available data. We held assessment WGs (AWGs) (Figure 5) that involved every player in each current or completed operation. The outputs of this forum fed directly back into the BFP and the reframing process. It was in this meeting where planners discussed the relevance of the data being measured with an eye to ensuring it contributed to the planning process. Generally this heated conversation led to a better understanding for everyone as the environment continued to change based on our actions.

Success in the assessment phase is defined by the brigade commander’s ability to articulate refined guidance to his or her subordinate commanders. Also, establishing the correct battle rhythm for the assessment phase is important to remain relevant in the current fight. However, the staff quickly determined that maintaining the same frequency of the meeting was less important than ensuring that assessment measures were correct. As time passed, the environment changed and became more complex as the actors in the system reacted to the brigade’s actions. Changing a meeting time and the inputs from the staff and subordinate units are extremely disruptive, but it ensures relevant meetings that focus on the changes that require updated assessment measures. Without adapting to the environment, meetings lose their substance and no one, especially commanders, are gaining anything from the information being presented because it is no longer relevant to the environment.

The brigade staff designed the BFP to match the brigade commander’s personality and benefits from an inherent ability to ensure that everyone got all the information and data available. This was made possible because of the physical structure of the fusion cell, also doctrinally called Plans. Only two areas existed in the brigade headquarters: the Joint Operations Center for current operations and the fusion cell for planning. Walls were literally knocked down and individual offices removed, preventing a stovepiped organization among the staff and creating a bay office where every WfF section worked.

Another technique used to ensure that information was disseminated as widely as possible was resourcing each battlespace integrator (battalion), combat advisory group (company) and security-force advise-and-assist team (SFAAT) with a videoteleconference capability, allowing anyone to join any meeting to provide their direct input.

Reframing and frequency

At any point during the BFP, conditions on the ground were likely to change, creating unforeseen circumstances, new opportunities or a renewed understanding of the environment. BFP’s iterative design allowed the staff to reframe if required. If there were no major changes in the environment, the staff would conduct the design WG on a recurring basis to determine if the key inputs – IR feedback, CUBs, BUBs, CABs – had revealed gaps in our understanding that require more analysis.

Whether the output of the design WG was to frame an initial problem, reframe based on changes in the environment or validate existing opportunities, determining the BFP’s frequency is important but not paramount. The BFP may be conducted on a two-, three- or even four-week cycle or planning horizon, with traditional “targeting meetings” occurring multiple times within each BFP cycle. Essentially, there is no defined cycle for the BFP. The environment and the brigade commander’s personality determine the process’s necessary tempo.

Conclusion

Throughout the BFP’s development and implementation, the brigade staff found that many steps in the process were simply extensions of the way our commander viewed planning and problem-solving. Challenging the status quo, questioning shallow assumptions and adjusting the plan throughout execution were all characteristics the staff had to adopt. In doing so, the staff gained a much deeper understanding of the environment and was able to develop more detailed solutions to complex problems. When finally presented to the commander as recommendations for decision, the gaps in understanding were narrower, confidence in the process was higher and the desire for action was greater.

The Bastogne Brigade’s 2012-2013 deployment to Afghanistan provided a unique opportunity to validate the BFP. The brigade’s security-force advise-and-assist mission created distinctive and nontraditional problem sets where a shared and accurate understanding of the environment was essential to properly apply limited resources in a geographically complex region. The BFP became a collaborative and iterative approach that significantly altered the way the staff viewed planning and problem-solving. The ability to become comfortable with being uncomfortable was essential in providing the commander the information he desired in a format that supported his thought processes.

We don’t expect that anyone will completely adopt the BFP as their method. Instead, it is our desire that this article has emphasized the importance of finding a process your commander is comfortable with, addresses the complexities of the modern environment and improves the ability to create a shared understanding. In the end, it is the active dialogue between commanders – company, battalion and brigade – and the staffs that highlight the BFP’s benefits.

Notes

1“Opportunities” within the BFP are defined as those areas where additional focus and effort can have a significant positive impact toward achieving the desired endstate.

email

email print

print