Partnership at Troop Level is Essential Element in Joint Distributed Operations During Drawdown Transition from Counterinsurgency to Foreign Internal Defense

A case study based on the experience of a battlespace owner in Kandahar City, Afghanistan, during Operation Enduring Freedom 12-13 and on combat-adviser experience in Sadr City, Baghdad, Iraq, during Operation Iraqi Freedom 08-09

The wars in Iraq and Afghanistan over the last decade – Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF) and Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF) – have used counterinsurgency (COIN) doctrine. Solidified at U.S. Army Training and Doctrine Command, first usage of COIN doctrine was during the surge in Iraq and then in Afghanistan. However, at some point in operations, we must transition from COIN to foreign internal defense (FID); we do this with less success because of a gap in doctrine.

Please note that in this article, I speak from my experience in operations before COIN was implemented (OIF 2005-06) and during COIN employment in the transitional drawdown to FID (OIF 2008-09 and OEF 2012-13). My transitioning experience in drawing down these wars came during OIF 2008-09 as a military-training-team (MiTT) member combat adviser, advising an Iraqi army brigade in battlespace control of Sadr City, Baghdad, and more recently, as a battlespace owner (BSO) commanding a cavalry troop in Kandahar City in OEF 2012-13.

Combat advising

During OIF 2008-09, Multinational Forces-Iraq (MNF-I) set June 30, 2009, as the day U.S. forces would “be out of the cities,” allowing Iraqi forces to take the lead. Similarly, during OEF, the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) set July 1, 2012, as the official Afghan National Security Forces (ANSF) “in the lead” day.

Consequently, MNF-I went from two brigade combat teams in East Baghdad during my tour in OIF 2008-09 to two battalion-task-force elements with five brigade-level MiTTs and one division-level MiTT. The maneuver units’ key task became strategic overwatch, with U.S. forces ready to: 1) reinforce Iraqi units to target insurgents and 2) enable Iraqi units as a quick-reaction force against their forces’ strategic failure. In essence, the task was to allow Iraqi forces to maintain the lead while ensuring their success at security operations. I will not divulge the specifics of the conflict set in Kandahar City, but a similar effort is taking shape; the notable difference is that the ANSF is able to maintain the relative stability maintained by previous ISAF units even through the “fighting season.”

The U.S. Army eventually answered this change in tasks as it took on the topic of combat advisers, restructuring MiTTs’ role into security-force assistance teams (SFATs). These redesigned teams are made up of more field-grade officers and fewer company-grade officers. SFATs were tasked with the responsibilities of advising and assisting the higher-echelon partnered forces while relying on the brigade to provide a security element for the team.

Another change was the SFAT’s pre-deployment training. SFATs began to train with the deploying brigade before deployment (MiTTs did not train with the brigade or coalition forces unit they would work with before deploying). However, both the SFAT’s and MiTT’s primary mission is the same (and therefore training should be similar): they are in working partnerships and advising roles with foreign security forces in the security line of effort (LoE).

Since our transition point to drawdown is a critical point in time, the questions I want to discuss or provoke thought on are:

- Why are strong partnerships essential in transitioning at the troop- and combat-adviser level?

- What are joint distributed operations (JDOs), and how can partnerships and enablers “bridge the gap” from COIN to FID?

- How do we transition between COIN and FID?

- How does the troop or company commander and SFAT chief task-organize for the mission?

- What tasks should pre-command captains focus on while in the Maneuver Captain’s Career Course (MCCC) to prepare for this mission?

Definitions

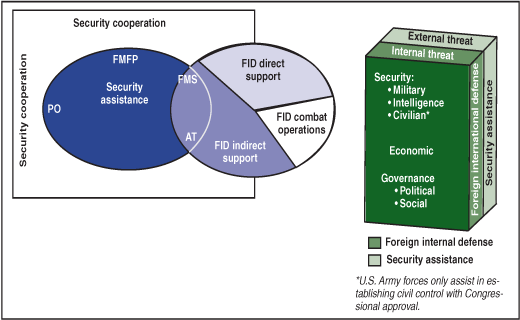

Before we can discuss transitioning from COIN to FID, JDOs or irregular warfare, we have to agree on the doctrinal definitions of each. (Figure 1.) We need a basic understanding of terms in relevant readings that include joint terminology and doctrine such as Joint Pamphlet (JP) 3-24. David Kilcullen’s “28 Articles” and David Galula’s analysis on insurgency and cultural information provide an understanding of the insurgency but also that of partnership and its importance in a transition to drawdown.

Similarly, the human terrain is paramount in COIN success in that the indigenous population must trust the coalition forces as well as the host-nation forces more than they trust the insurgency. As these concepts are not hard to comprehend, most barriers to implementing a successful campaign through transition are commanders or combat advisers who are unwilling to take the necessary steps to ensure a strong partnership at their level. Partnership is the quintessential element that enables the BSO or combat adviser to transition the host nation into the lead.

Questions/discussion

Why are excellent partnerships essential in transitioning to drawdown for company/troop teams and combat advisers?

Before a host nation is able to lead security operations, the higher command (battalion and above) must facilitate the host nation’s ability to take the lead. Previously, when brigades and divisions deployed in the war on terrorism to OEF or OIF, they prepared for their specific mission(s) in a specific allotment of time – the unit’s endstate did not envision the war’s endstate and thus the eventual handover of security and all other LoEs to the host nation. This shortsighted viewpoint led to weak or non-existent partnerships between host-nation forces and BSOs and/or combat advisers. Intuitively, success for the host nation is paramount. When the BSOs’ primary concern was that of their own statistics, or tasks associated with securing themselves, host-nation forces were unprepared for the demands of combat once transitioned to the lead.

Much of the effort to enable our host-nation partners rests on the personalities of the BSO commanders and combat-adviser teams (MiTT or SFAT) in a unity of effort across the operational environment (OE). If commanders or combat advisers are not willing or able to make the partnership work with the host nation, the next unit will have to fix it, leaving the deployment with an endstate of failure. Granted, as a BSO there are many tactical gains achievable on our own without enabling the host nation and, for some BSOs, that is their only reward. However, what is the point of losing blood and treasure on these tactical gains if the gains are not sustainable and transferable?

In this state of transition, commanders and platoon leaders must carefully match as partners to our foreign counterparts. Otherwise, they can easily deteriorate what may have been a strong partnership if they do not have the right adviser-like qualities. (Figure 3.) Commanders must embrace these qualities since the transitioning-phase BSOs will provide overwatch and work closely with the host-nation forces. Also, depending on the number of partners and the OE’s size, operational gains can be multiplied by working together and dividing security tasks with the host nation.

When you start working with a new partner, you must complete a certain amount of reconnaissance to assess your partner’s capabilities. Once you determine strengths and weaknesses, you can make a training plan to help improve their weaknesses and initiate a planning effort to take advantage of their strengths. An example would be a host-nation police unit that is excellent at checkpoint operations but lacks tactical knowledge on conducting dismounted patrols in an urban environment. A simple patrolling class can be assembled to help the host-nation police develop their dismounted patrolling techniques while a sizable amount of the partnered force maintains checkpoint operations.

Equally, the higher command must ensure similar units are partnered – for instance, partnering a military-police unit with an Afghan police unit and an infantry company or cavalry troop with an Afghan National Army unit. A structure such as this will prevent maneuver units from conducting maneuver operations with a police unit, for which the police unit would not be prepared or equipped.

Another example would be that of police units who use warrant-based operations, whereas our military-intelligence cells do not – instead they use targeting to interrogate suspects. Unfamiliar with military-intelligence tactics, the partnered police units may be hesitant to detain someone without actual evidence that uses the rule-of-law process they are trying to follow. Ensuring we leave the host nation with sustainable gains entails that we continue to facilitate our partners’ education and training.

Certainly, participating in joint patrols with your partners builds trust in the relationship that both units are willing to maneuver through the same dangerous areas together. However, there are pitfalls in only performing joint patrols, as the perception that we are untrusting of or unwilling to allow our partners to take the lead may solicit host-nation resentment of us. Therefore, it is important that host-nation forces are planning and leading patrols. This demonstrates that you will follow their lead and will build your “wasta” with your partners. Therefore, our forces must not just “show up” for the mission; although other forces’ pre-mission planning is less deliberate than our troop-leading procedures or military decision-making process, one must remember it is their mission to lead and our role to support as necessary.

Empowering the host nation to conduct missions means relinquishing control but respectfully continuing to give advice. Using degrading tones and insults – especially in front of subordinates – or any other demeaning management style in a partnership will never work in this effort and simply works against the endstate. I have personally witnessed these negative types of partner relationships by BSOs and combat advisers, and they certainly do nothing to help either party – and probably lead to negative green-on-blue instances (or vice versa). In light of the current situation, another advantage of a strong partnership is the likelihood it will decrease green-on-blue incidents; a close partner would not allow this to happen.

Ultimately, having strong partnerships works toward the ultimate endstate of the host nation’s full control, but for that to happen, the host nation must take the lead. A unity of effort of all BSOs and combat advisers must constantly be working toward that goal.

How do we transition between COIN and FID?

The widespread use of COIN doctrine as a U.S. military effort has only come about during the war on terrorism, although it certainly existed before that. One of the major differences between COIN and FID is that military power in COIN involves the use of many conventional forces, whereas FID relies mostly on a small conventional force and Special Forces or “other governmental agency” (OGA) capability. Both include an array of OGAs’ involvement, but as with the military in COIN, the Department of State (DoS) and U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) package is much larger during a COIN effort. With both OEF and OIF, a large portion of the international community was involved, helping along all LoEs; this adds to the host nation’s credibility.

In both OIF and OEF, COIN involved a surge of forces, with focus on the security LoE, which gave the host nation the capacity to train an armed force to assume the security LoE once the surge was complete. Working in concert during the surge, we focused on the governance and economic LoEs as well, with the stabilizer being security. Another major difference in FID is that the host-nation government is mostly in control, and the level of subversion is less, so that a smaller element can help with the problem. Unfortunately, as seen in both OEF and OIF, a complete revamp of all governance – rebuilding these countries from the ground up – was necessary.

The rationale in transitioning from COIN to FID is the premise that the host nation – with some assistance from the supporting coalition – is strong enough to maintain control and the lead on all LoEs (governance, security, economics). The ability to do this is created by a surge of forces that enable the host nation to build capacity. Moreover, this capacity created by the surge of conventional forces is where many of the governance and economic LoEs are able to expand their influence.

Correspondingly, the surge presents an opportunity for the coalition and local populace to build an enduring relationship built on trust. The host nation’s people must believe that coalition forces are trustworthy and will protect them from insurgent retribution. The host nation must recognize that when coalition forces hand over responsibilities, ensuring its local populace is protected from insurgent activities must remain the highest priority – if this happens, trust is created and subsequently strengthened between host-nation and coalition forces. Unfortunately, there have been a few instances where individuals or small groups of service members have created doubt as to what our priorities are as portrayed in the media.

In the big picture, to move into the FID role, a capable governmental, economic and secure state that has the people’s trust must be in place. Once capable-government capacity is reached, partnerships can be passed from the bottom up, starting at the company/troop level through combat advisers to eventually draw down coalition ground forces to let host-nation forces begin to lead.

With these drawdowns comes a massive supply exodus of equipment out of theater. Since the coalition governance, Special Operations, intelligence and combat-adviser elements are already operating in theater during COIN, there is no need to push more assets into theater, as they are already there. Simply put, removing larger conventional forces accelerates a FID operation if stable conditions for host nations are set.

What are JDOs, and how can partnerships and enablers “bridge the gap” from COIN to FID?

For the first time in military history, the conventional military has adapted largely over the last decade to using more enablers in operations. Previously, preparing units for war meant most units had very little in the way of enablers at company or troop level – or even at the battalion level. For instance, it was unprecedented that at the troop, company or battalion level, the unit became involved in LoEs such as the influence of governance or economics. Before deployment, units were allocated with the necessary equipment to complete the tactical tasks they were assigned.

In addition, we had to enable units to fight along all LoEs, and much of this was not kinetic fighting. Progression was necessary not only in security but also in the economic and governance LoEs. Fortunately, JDO allows the smallest command element to fight across all LoEs. A company or troop in a JDO has added enablers normally used at the battalion level or higher to facilitate the unit in fighting along all LoEs.

The station a JDO must occupy requires that the company or troop element must be physically located away from the battalion headquarters. Seen in both OIF and OEF with the implementation of COIN were the use of an array of platoon- or company-level combat outposts (COPs) – i.e., joint-security station or personnel-security support (PSS), depending on the operation. In essence, COPs allowed company- or troop-sized elements or smaller to operate in and among the people thereby providing security in an area, whereas prior to COIN doctrine, units would “drive to work.”

In my last deployment as a combat adviser, I worked with Company A, 2-5 Cavalry, in Sadr City, who had more enablers in the JDO than any other JDO I’ve personally witnessed. The level of priority and the foreseeable impact that success in Sadr City would have on the war were the reasons that enablers were added to this specific OE. The JDO to which I am referring was a COP near Sadr City that included an infantry company, MiTT, provincial reconstruction team (PRT) (DoS or USAID), civil-affairs (CA) team (CAT), tactical psychological-operations team (TPT), human-intelligence control team (HCT), aerostat (balloon with camera) and multifunctional team (MFT) (signals intelligence), who worked together along all LoEs to transition to a drawdown of coalition forces and to enable Iraqi forces. Likewise, this company regularly supported Special Forces missions in the OE that conducted targeted kinetic raids with Iraqi forces. Subsequently, Company A was the main effort for MNF-I during this tour to OIF and was the premier example of what JDOs can accomplish.

For instance, in East Baghdad in January 2009, there were two brigades that decreased to two battalions by July 2009; more enablers were added to the company to help maintain the coverage of intelligence assets and to enable host-nation partners. Eventually during a drawdown, the sharing of intelligence assets must occur, but there is a very delicate balance of what intelligence assets we are able to share with our host-nation partners to enable them to assume the lead as we slowly decrease our operations. As the transition initially starts, coalition forces sharing enablers – combined with the human intelligence our host-nation forces have – many times will yield initial tactical-level victories, as the enemy never expects when the host nation will gain these advantages.

When most units prepare for deployment, they do not train with this variety of enablers at the company/troop level. Most will only see a select few of these during a deployment. Since the employment of COIN doctrine, most units have a company intelligence-support team (COIST), who works to provide intelligence information up and down the chain of command as well as left and right to other company-/troop-level elements around the battlespace. Pre-deployment training at combat training centers (CTCs) conducted at brigade-and-below mostly focuses on the maneuver unit’s ability to shoot, move and communicate. There is not enough focus on a unit’s ability to master the art of COIN with joint-enabler assets in the JDO. Unless there is prior experience within the JDO, learning to operate in the JDO will usually be conducted in combat. Some of these enablers are rare, so the military is unable to train with these elements before deployment; a large step in the right direction is with SFATs and their rotation to CTCs with conventional units.

One large difference between embedding assets from OIF to OEF is that PRTs, CA and TPT were not embedded in parts of OEF, whereas in OIF they were almost always embedded. Embedding these enablers is a key step to improving along the governance and economic LoEs because it 1) allows the PRT to see the problem sets from the closest battlespace and 2) allows the team or enabler to get the common operating picture. Embedding enablers at the lowest levels follows COIN guidance from JP 3-24 (DoD follows this, but DoS and USAID do not), so one must ask the question: in COIN-like wars, should DoS and USAID have to follow certain DoD joint doctrine when it comes to embedding to improve unity of effort? COIN was more efficient in OIF than OEF from the PRT perspective simply because PRTs were embedded. This does not only apply to PRTs in OEF but enablers as a whole. While OEF is still a JDO, it is more degraded because of the lack of enabler distribution to lower-level maneuver units, even in key terrain areas.

Joint patrols with partners is one area in which joint enablers can demonstrate to our host-nation partners the advantages of what our enablers bring to their forces. These enablers help improve survivability and, as research suggests, allow us to defeat the enemy. Furthermore, enablers can be requested by all units maneuvering the battlespace, but are ever-changing with the enemy’s changing tactics. For example, since the war on terrorism began, we have gone from using the standard unarmored humvee to upgraded mine-resistant, ambush-protected vehicles. In addition, enablers can include unmanned aerial vehicles, mine detectors, air-weapons teams, MFTs, HCTs, EOD, route-clearance teams (RCTs), intelligence-surveillance-reconnaissance, TPTs, CATs, Special Operations forces and more.

How does the troop/company commander and SFAT chief task-organize for the mission?

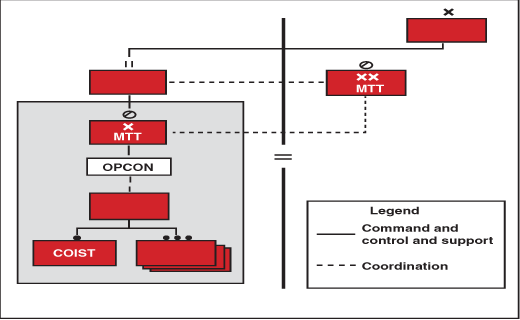

Task-organizing for drawdown transition is a phase where the guidance from higher can be somewhat murky (at best). There is little doctrine to go by, and where there is doctrine, it is limited. Field Manual 3-07.1, The Modular Brigade Augmented for Security Force Assistance, provides the best way forward on how this should work, despite the manual’s limited details. Ultimately, it is the brigade commander’s decision on how to task-organize units. Figure 7 shows a company element under operational control (OPCON) to the transition team.

There are a couple of different ways to task-organize for the mission to a company element: OPCON, tactical control (TACON) or direct support to the SFAT or MiTT. I have seen all three types of control, and all can work. In some cases, the SFAT chief is the BSO over a task-force-like scenario. In my case, the SFAT chief served as the ad hoc battalion commander and is the O-5 level of clearance for all units a normal battalion commander would serve. In any situation, there is always push-and-pull from the SFAT chief’s roles and responsibilities to the company or troop through the normal battalion chain of command.

As a troop or company going into this mission, you will either be tasked with direct support, OPCON or TACON, or will be responsible to an adviser chief who partners at the next level above the company or troop. In any case, there is limited training where a company or troop can prepare for these scenarios, and these command relationships are not developed until deployment despite the SFAT’s arrival at units before CTC rotations and deployment.

What tasks should pre-command captains focus on while in MCCC to prepare for this mission?

There is very little instruction dedicated in MCCC to the actual transition phase of a COIN effort. The company-level operations-order phase that focuses on COIN is much more involved in tactical maneuver than in the subtleties of advising foreign forces. However, for a company or troop that will be OPCON, TACON or direct-support to an SFAT, one can think about a few common tasks.

One of your platoon elements will be dedicated as a security force to the SFAT, and that will take away a platoon of combat power, or roughly 15 Soldiers at minimum. When you deploy, your company or troop will still have to occupy the tactical infrastructures for force protection or base defense, and this will most assuredly deplete combat power. What is left after that is usually what the company or troop has to conduct actual partnered patrols and missions.

In addition to being tactically proficient at cordon and search, clearance operations, tactical checkpoints and air assault, it is also good to be proficient at key-leader engagements, shuras, negotiating and even being prepared to run a training course on our “shoot, move, communicate” task to host-nation forces. During a drawdown, as discussed earlier, there most likely will be more enablers accessible to the company or troop than in other situations. However, one cannot guarantee this; thus it is always prudent to obtain as much information before deployment on the capabilities and limitations of joint enablers so they can be more efficiently used. For instance, having the company or troop go through cultural-awareness training for the area of deployment will also make a well-trained team that can appreciate the local populace’s customs and norms.

Lastly, during a transition to drawdown, the only way to gain trust with the local populace and partnership with security forces is to maintain the moral high ground. If there is a hint of corruption detected by either entity, trust will be lost.

Conclusion

OIF and OEF have both followed the same general COIN template during the war on terrorism; through technology, we have been able to record the data points for both of them more accurately than for previous wars. Partnership at all levels, with unity along all LoEs, is the key factor to moving the transition of COIN forward to FID. However, there is still a large doctrine gap in what is expected of company or troop elements, particularly when working under an SFAT chief and in training that would best enable a troop or company commander to be successful during a transition to drawdown.

Joint enablers allow higher-level commands to remain as involved during a transition to drawdown as they were before the decrease in units. Joint enablers also allow company or troop elements to continue to push momentum forward across economic, governance and security LoEs while a transition to drawdown is taking place.

Moreover, at no other point in a war is restraint as important as during the drawdown. It is especially important to let the host nation carry the fight in an overwatch status to assess its effectiveness. Maneuver commanders must restrain themselves from going out and initiating conflicts while championing their counterpart’s lead role during the battle. The U.S. maneuver commander must ignore his basic instinct to fight if an opportunity presents itself; instead, he must somewhat assume a backseat-view understanding – to leave a thriving security force, it is imperative to let the host nation lead the fight before our exit and transition to FID.

If more commanders knew the importance of how to employ JDOs and how important their partnerships with their host-nation counterparts are, the more successful they would be in conducting a transition from COIN operations to FID during a drawdown.

email

email print

print