How We Got Here and Where We Are Going: a Doctrinal Approach to the Health of the Force

The Army’s health of the force (HoF) has been in a steady decline since combat operations in Afghanistan began almost 12 years ago. In the past nine years, suicide and divorce rates have risen at an alarming rate. In addition to this, drug and alcohol, financial and legal issues continue to plague the military. Recent Department of Defense initiatives have had a slight impact to reduce these trends, but even as deployments decrease in Afghanistan, crises and catastrophic events will continue to increase unless leaders find a way to be proactive and identify issues before they escalate further.

The bottom line is that leaders must reconnect with their Soldiers and really know them to apply risk mitigation to the individual Soldier and family. Using a doctrinal mission-essential task list (METL) development approach, the troop commanders of 4th Squadron, 3rd Cavalry Regiment created a HoF METL that outlines battle tasks to the individual level and sustains an enduring operation that enables a better understanding of our Soldiers.

Background

Vice Chief of Staff of the Army (VCSA) GEN Peter W. Chiarelli conducted tours of six installations in 2010 with the purpose of looking at how the force was dealing with the increase in suicides. He determined the Army was out of balance concerning health promotion, risk reduction and suicide prevention programs and services. What he and his staff witnessed firsthand was that there were “real indicators of stress on the force, and an increasing propensity for Soldiers to engage in high-risk behavior.”1

Chiarelli realized that leaders could not target suicide prevention alone and that the Army must look at other factors to be successful. To reduce these problems, the Army needed a holistic and multi-disciplinary approach to address each issue. Also, leaders at every level must practice an engaged leadership style. The Army Health Promotion Risk Reduction Suicide Prevention Report (Red Book) confirmed the need “for a coordinated effort across the Army to promote good order, discipline and health of the force.”

GEN Lloyd J. Austin III, the current VCSA, recently said: “Leaders across our Army recognize that the health of our Soldiers, Army civilians and family members is a top priority. We remain committed to doing what is needed to care for our most precious asset — our people — thereby ensuring a healthy and resilient force for the future.”2

More than a decade at war, resulting in a high operational tempo, meant we had less time to dedicate to HoF. This has led to knowledge gaps in our systems concerning how we identify, engage and mitigate high-risk Soldiers. There are many reasons why knowledge gaps have formed. For example, there has been a breakdown at military schools on negotiating the art of leadership in garrison. Policies, processes and programs have not kept pace with the expanding needs of our strained Army. This has led to a population of high-risk Soldiers who erode Army values and unit readiness.3

Also, Soldiers and families are feeling the stress of a decade at war and multiple deployments. According to the Army Red Book, “The cumulative effect of transitions borne of institutional requirements (professional military education, permanent-change-of-station moves, promotions), coupled with family expectations / obligations (marriage, childbirth, aging parents) and compounded by deployments is, on one hand, building a resilient force while on the other, pushing some units, Soldiers and families to the brink.”4

It is readily apparent that leaders at all levels are not engaging Soldiers to the level that would adequately identify associated risk. Also, we are not leveraging the multitude of available established resources required to build a holistic picture of the Soldier. As a result, leaders are uninformed or do not understand the connectivity and the risks of crises and frictions. Leaders must be aware of all these aspects of their Soldier’s lives to know them better. Entrusted in our care are our nation’s sons and daughters. Despite our optempo, we must not neglect this monumental responsibility.

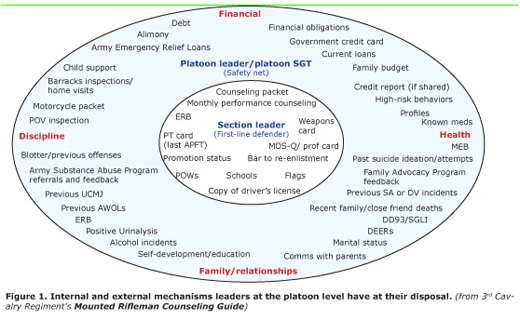

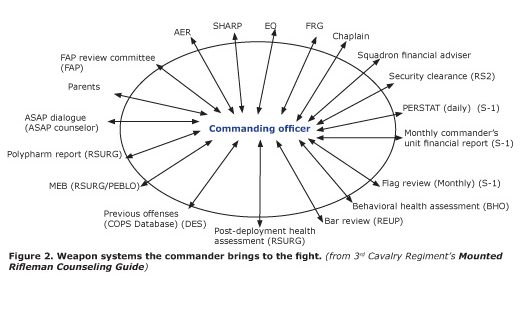

Commanders in our squadron used a tool called “connecting the dots” to know our Soldiers. The “connecting the dots” tool was created by the 3rd Cavalry Regimental staff as part of the regiment’s ongoing HoF campaign and as a part of the regiment’s Mounted Rifleman Counseling Guide. Depicted in the figures are the “connecting the dots” tools that Longknife Squadron used. Figure 1 depicts the internal and external mechanisms leaders at the platoon level have at their disposal. Likewise, Figure 2 portrays the tools a commander and first sergeant can use.

Recent trends in our regiment resulted in our regimental commander issuing a HoF, resiliency and leader-development training period so we could assess trends and issues with our Soldiers. We found out we did not “know” our Soldiers. There is only so much that monthly counseling can do to help leaders understand their Soldiers, especially if done on the margins and when commanders to not emphasize or dedicate the appropriate time. Unless you comprehensively immerse yourself in your Soldier’s life, you will never fully know your subordinates.

You have to learn to ask the tough, uncomfortable questions that get to the root of the friction. Through the HoF campaign, our squadron assessed nine more high-risk Soldiers. This was a result of us connecting the right dots. Our Soldiers realized we now had a stake in the HoF campaign and in our Soldiers, which fostered a climate conducive to candidness, honesty and trust between leaders and subordinates. Soldiers were increasingly open with leaders about their personal lives, thus allowing a collective core of responsive and caring leaders to act in a proactive manner and leverage appropriate agencies and resources to help Soldiers and families in need. Without these measures, we would not have been able to identify that these additional Soldiers within our formation were at high risk.

Thus, we were able to identify the problem facing our junior leaders at the company, platoon and squad level: How do we assess HoF within our organization? No tool in the Army exists that gives you ability to address this issue. There are tools out there to aid commanders in understanding our Soldiers (Gold Book, Red Book, etc.), but there is currently nothing structured to give direction and understanding of where an organization stands in terms of taking care of its Soldiers. The squadron began to develop a METL devoted to HoF as a systematic approach to better assess and identify gaps in engaged leadership in our organizations.

METL development

All units have a METL that guides their warfighting training strategy. The doctrinal-based METL all units must train on is the core mission-essential task list (CMETL). “A CMETL is a list of a unit’s core-capability mission-essential tasks and general mission-essential tasks. Units train on CMETL tasks until the unit commander and next higher commander mutually decide to focus on training for a directed mission,” according to Army Doctrine Publication (ADP) 7-0.5 Most units can review their CMETL through the Combined Arms Training Strategies (CATS) viewer on the Army Training Network (ATN) Website.

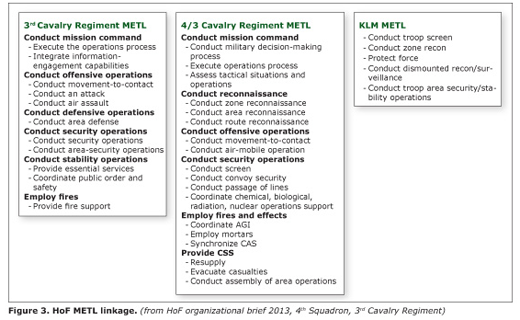

After reviewing their CMETL, commanders choose which tasks they are going to train, ensuring they are nesting within the squadron CMETL. METL development is the process of deciding which of the available tasks must be completed to accomplish the overall mission. Figure 3 depicts our regiment’s nested METL.

The three reconnaissance troops within 4th Squadron, 3rd Cavalry Regiment, established a METL nested within the squadron’s METL and determined which collective tasks to train. By following this process, commanders created specific guidance for what needed to be trained to meet mission requirements.

The commander finally plans, resources and coordinates for the training necessary to allow the unit to gain proficiency and meet established higher-echelon training gates. Again, the CATS viewer on ATN helps by providing performance measures for each METL collective task, and example situational training exercise and live-fire exercise evaluations for each task. Commanders ensure their unit is well trained by following the doctrinally approved METL and performance measures.

METL development in HoF context

As new commanders, one of the highlights of command was when our squadron commander empowered us with the autonomy and trust to develop our troop METLs. We then applied lessons we learned in METL development of our wartime mission to developing our HoF METL to quantitatively evaluate our organizations, and we challenged ourselves to understand each of the HoF METL tasks completely, starting from ground zero.

What started with mere thoughts on a whiteboard soon became an organizational vision and initiative from our squadron commander. The squadron senior leadership developed four squadron HoF mission-essential tasks:

- Health and discipline surveillance and detection;

- Health promotion and referral;

- Administration and disciplinary actions; and

- Good order and discipline.

This was fundamental for the HoF METL development campaign. The squadron commander brought the troop commanders into the squadron conference room and provided us:

- The regimental commander’s guidance;

- The Mounted Rifleman Counseling Guide;

- Army Gold Book;

- ATN;

- Army Regulation 600-20, Command Authority;

- AR 6-22, Leadership; and

- The squadron HoF METL.

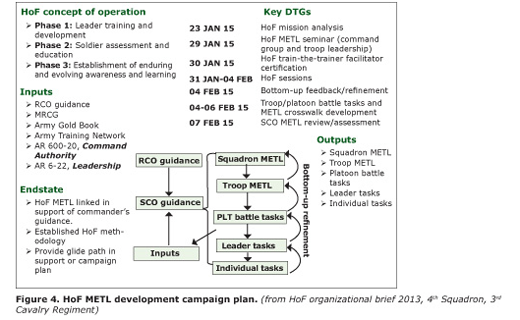

He then tasked us to develop a troop HoF METL that was nested within the squadron HoF METL and a comprehensive METL crosswalk reflective at the platoon, section, leader and individual levels. Figure 4 depicts our HoF squadron campaign plan.

Due to a determined and professionally enlightened dialogue among the troop commanders, we established five troop-level HoF METL tasks (discussed more, following) that nested within the squadron METL:

- Execute command authority;

- Conduct fit-for-duty assessment;

- Integrate internal and external enablers;

- Facilitate rehabilitation or transition; and

- Sustain a positive organizational culture climate.

Figure 5 depicts the troop-squadron HoF METL linkage.

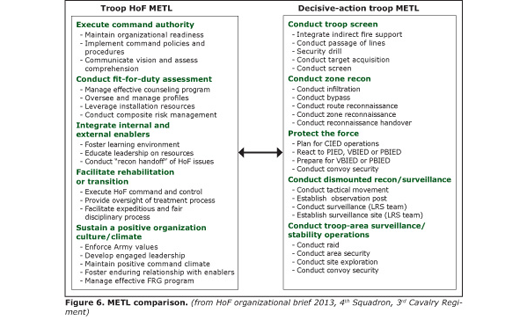

It was important to draw from our decisive-action METL the appropriate action words and create mirrored verbiage between the two METLs. We ensured leaders at all levels of the organization understood the HoF by using the appropriate action words. (Descriptive action words enable us to better understand the tasks.) Figure 6 displays how the action words are relative between the HoF and tactical METL.

Listed following are the troop HoF METL tasks we developed. These are the most relevant tasks that allowed us to understand our Soldiers better. The great thing about METLs is they are adjustable to different units. These tasks can easily change from one organization to another.

Execute command authority. As commanders, we have the privilege of command authority, and with that authority comes great responsibility. How commanders handle responsibility has a profound effect on our organizations. The policies and procedures we implement shape the organization as well as the vision we project. The magic word for commanders is “readiness.” How we maintain readiness as an organization, in terms of training and keeping our force healthy, is paramount to our ability to be successful in combat.

Conduct fit-for-duty assessment. We cannot effectively support our Soldiers unless we truly know and holistically understand the individual. Effective counseling is the key when conducting fit-for-duty assessments. Only through engaged leadership and leveraging all available resources can we better support and care for those within our ranks.

Integrate internal and external enablers. Our military installations do a fantastic job of offering our Soldiers a myriad of facilities and resources in which to receive help and support. Too often, leaders do not fully understand or are unaware of the different enablers present on various posts. We identified this as an issue that prevents Soldiers from receiving the appropriate support for the various stressors in their lives.

The knowledge of what the installation has to offer is only the beginning. To best support our Soldiers and their families, we as leaders must have a dialogue with the provider, counselor or individual involved in helping our Soldiers. Only then can we truly streamline the assistance the Soldier is receiving and respectively increase their resiliency. It is a collaborative effort between the commander and the provider.

Facilitate rehabilitation or transition. Our job as commanders is ultimately to manage the operational readiness of our unit. It is our responsibility to identify Soldiers needing to transition out of the Army or transfer to a unit better able to assist them in rehabilitation. Leaders at all levels need to understand the completion of tasks that are necessary to provide the unit with a timely transition of the Soldier out of the unit or rehabilitation back into the force. We must be cognizant not of the health and well-being of the Soldier but of the unit’s health and the damage done by delaying transition or rehabilitation.

Sustain a positive organizational culture / climate. This is the decisive task of troop HoF METL – the foundation around which HoF is centered. It is important to note the difference between a unit’s culture and climate. The climate is defined by the command team and will change when leadership changes. The culture is enduring and inculcated among Soldiers in the unit. The culture of an organization is much harder to change and will most likely survive the turnover of leadership. We strive to create not only a positive command climate but also a positive culture – one able to withstand poor leadership when it inevitably occurs.

To make an effective product, a leader must obtain bottom-up feedback, allowing for Soldier and organizational buy-in. Once we had solidified the troop HoF METL, we introduced it to the leadership within our ranks. We brought in our platoon leaders and platoon sergeants and began the development of realistic platoon-level “battle tasks.” Where we deviated from normal METL development was in the creation of a “leader” task. Leaders of all levels within our organizations must execute these tasks to be successful within the framework of our HoF METL.

The leader tasks proved to be easier than the initial troop METL tasks to identify because we received input from the individuals who execute HoF tasks every single day – they just had never put a name to it. We again deviated from normal METL development process by not crosswalking each task down to the individual level. Quite simply, we identified that some tasks would not have an associated section or individual task. Upon completion of our backbrief to the squadron commander, we arrived at a nested and aligned troop METL consistent with a crosswalk down to the individual level.

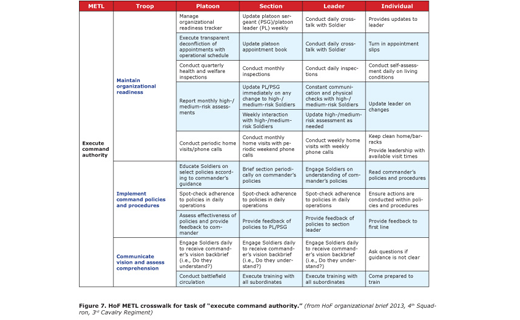

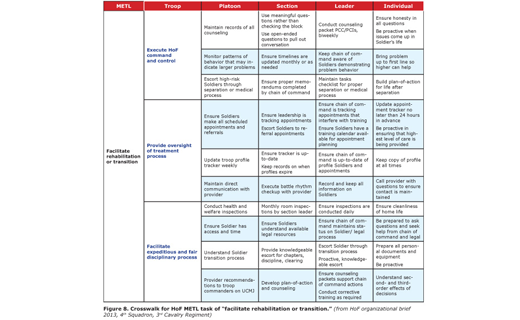

Figures 7 and 8 depict the troop HoF METLs of the tasks “execute command authority” and “facilitate rehabilitation or transition” with complementary collective, leader and individual tasks.

Conclusion

HoF is important not only to the Army but to the military as a whole. Unless leaders ask the hard questions and spend time getting acquainted with our Soldiers, we will never really know them. When we do not know our Soldiers and what issues they have, we are doing a great discredit to our Soldiers, their families, the Army and the nation. By adopting a similar approach to our HoF campaign and creating their own HoF METL, leaders at all levels can increase their understanding of their Soldiers and identify any possible high-risk stressors or activities. What we were able to produce was a comprehensive, quantitative HoF METL we could use to assess both our Soldiers and organization. We developed a tool that provides us with an effective way to lead our troops safely. Without a healthy force, we will never achieve the operational readiness needed to fight and win our nation’s wars.

Our process leaves room to grow. It may not be the way, but it is a way we were able to use to better know our Soldiers and identify, then mitigate, risk in their personal and professional lives. Any unit in the military can take our process and adapt it to its own organization. As Chiarelli said, “We must all be vigilant of the perils associated with a stressed force. Leaders at all levels must stress accountability. You must continue to aggressively surveil, detect and intervene to, first, promote health and well-being and then, second, reduce the risk to the individual and others.”6

The HoF METL development initiative has led to reinvigoration of leadership skills, validation of our counseling programs and understanding of our Soldiers. The HoF METL is the tool that allows us to survey, detect and ultimately intervene as leaders within our organizations.

Notes

1 Army Health Promotion Risk Reduction Suicide Prevention Report, 2010 (Red Book).

2 Frady, K., Suicide Prevention: a Healthy Force is a Ready Force, Sept. 4, 2012.

3 Red Book.

4 Ibid.

5 ADP 7-0, Training Units and Developing Leaders, August 2012.

6 Establishment of Army Campaign Plan for Health Promotion and Risk Reduction FY11.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook email

email print

print