Observations from the Opposing Force

This article is designed to assist the maneuver community as the Army continues to develop how it will fight in the new decisive-action (DA) format. The authors, two former troop commanders, are two of the most tactically proficient troop commanders when it comes to the basics of mounted maneuver. Both are combat veterans previously assigned to the National Training Center (NTC) when the first DA rotation kicked off and have been involved in its continual growth. Their article highlights many of the observations they made and capitalized upon, and which our current troop commanders now use to increase success on NTC’s battlefields.

The general observation is units that focus on the basics and understand doctrine are much stronger and more successful during combat operations. This also applies to units that have been able to identify and emplace training programs that make up for the current shortfalls of field training in the schoolhouse and the current atrophy of maneuver experience within the mounted force. NTC is committed to training excellence and, with that said, we all stand ready to help train the force. We will not give you all the answers out of loyalty to the Blackhorse Regiment/11th Division Tactical Group. Instead, we provide you with several ideas that have proven critical in mission success or failure. Take these observations into theaters of operation for deploying units, as they hit on commonalities in stories of success and failure observed in Iraq and Afghanistan in recent years. –LTC Frederick R. Snyder

Know your capabilities / shortcomings

As a troop / company / battery commander, you have to know your capabilities: which of your platoons is the strongest, which has the most aggressive leadership, who are the most capable gunners. More importantly, you have to know your shortcomings: which platoon has discipline problems (and how will that affect your mission), which platoon has maintenance issues (and why), who can’t figure out how to get out of the tactical assembly area.

Answering questions like these objectively will allow you to assign responsibilities to individuals and platoons based on capabilities instead of arbitrarily. Keep open lines of communication with your junior leaders. Inspect their training. Watch how they execute command maintenance.

One key factor enables each of these: command presence. Removing yourself from command maintenance or other training events – relegating yourself to an office troll – denies your troops your guidance and sets precedence for your junior leaders to do the same. For platoon leaders, this is especially important. Fighting your platoon is your responsibility and, as such, you need to know in every mission the distance at which each one of your vehicles is capable of destroying enemy vehicles (by type).

Be ruthless in the boresight battle rhythm. Know which gunners can kill at distance and who is better off keeping their shots to less than 1,500 meters (and needs continued training). This will allow you as the commander to place vehicles / personnel where they are most effective – where they can place precision, lethal fires on a one-shot, one-kill basis, ultimately conserving ammunition and reducing your exposure to enemy forces, especially in the defense. Direct fire control is the name of the game, and knowledge of your vehicle / personnel capabilities has to be part of your playbook.

Use your tools

In our age of technology, you should never enter a new area of operations blindly. If you do, shame on you. There are many accessible tools to enable you and your junior leaders to have a decent concept of the terrain you are entering well before you enter it. Maps are excellent tools, but graphics / imagery are better. If you cannot visualize the terrain and help your junior leaders do so, the enemy will have an early upper hand in the fight. They will likely know the terrain. Force XXI Battle Command Brigade and Below (FBCB2)-Blue Force Tracking (BFT) / Joint Capability Release (JCR) bring excellent situational awareness to the battlefield. Not only do these tools give you the capability of tracking your unit’s progress, they work great for mission planning and movement control.

Also, unclassified Websites like Google Earth and Hawgview give you the capability to “see” the terrain before you are sitting on it or driving through it. Seeing the complexity of the terrain through tools like these can prevent planners from committing blunders like attempting to send a combined-arms battalion through a maneuver corridor only capable of passing a section (true story) or placing a mounted defensive position in terrain that cannot be accessed by wheeled or tracked vehicles (another true story). Further, these tools give subordinate leaders much better situational awareness than simple maps can provide. They allow your team to visualize how the fight will be conducted and thus allow them to fight decision-point tactics.

Boresight, boresight, boresight

In Rotation 12-05, the first DA rotation at the NTC in years, Charlie Troop destroyed a significant portion of an advancing rotational training unit (RTU) battalion as they began to enter the central corridor. Poor tactics? Superior position? No and no. The RTU company / team leadership had decided not to boresight their tanks and Bradleys. Amazing. They had gone through a deliberate planning process for the initial brigade-level movement-to-contact, conducted troop-leading procedures from brigade to platoon level, backbriefed their leadership, executed rehearsals, etc. This company, no matter how well planned their mission was, no matter how well prepared they were (outside of boresighting), was completely ineffective.

How one would consider deliberately not boresighting acceptable is astounding, but the fact remains and has been observed many times on a smaller scale since then.

Any leader who has sent his troops to the range can attest to the significance and the results of quality preliminary marksmanship instruction training. If a Soldier does not boresight his weapon, he will likely see extended time, heightened frustration and a waste of ammunition on the range trying to zero and qualify. Take that idea to an Abrams tank or a Bradley when normal engagement ranges are around 10 times that of small arms. There are processes and techniques to boresighting that units must be able to execute quickly and to standard before deploying on field-training exercises and before individual missions. It is a Gunnery Skills Test standard that must be met for gunnery and, thus, should be considered a gate to a crew moving out to execute any mounted maneuver training.

Boresighting is essential to unit success and requires practicing multiple times per day. Add it to your battle rhythm. Execute it after any major movement and / or prior to any mission. It is a no-fail event.

Think red

For the staff, this means wargame. The commander cannot make decisions unless he has a good idea of how the enemy will fight. At the battalion / squadron level, this means acting out the battle from start to finish (and beyond) to understand what possible courses of action the enemy may execute; what / where / when the key decision points will come; and what the constraints are (by staff function and by warfighting function) to provide the commander with the best course of action to enable his intent and achieve his endstate.

At the company / troop / battery level, this means doing your homework. Understand the enemy: what is he bringing to the fight, what are his tactics, what are the capabilities of his weapon systems?

To understand how the enemy will fight, you must also understand the terrain. Get with your S-2 and build your modified combined obstacle overlay, your doctrinal template and your threat template. Put your red hat on and fight your battle in reverse. Where is the key terrain and how will it impact the fight? If you were the enemy, how would you move – would you sacrifice security for speed, or would you hold up to secure dominant terrain? Where and when would you be vulnerable?

Be prepared to discuss a thorough enemy situation in your order and during your rehearsal. A common understanding of the enemy’s disposition, task and purpose will enable your subordinate leaders to understand the order of battle, feed your information requirements and initiate / react to contact when the battle comes. Do not shortchange your junior leaders or yourself with a substandard enemy picture or a weak rehearsal.

Get outside the wire and walk / drive the perimeter

You would not believe how many units occupy a defense, set in their positions or conduct engagement-area development without “leaving the wire.” At NTC or in a theater of operations, you may occupy a forward operating base, joint security station or patrol base that has a full perimeter with defensive positions already established. Consider this a gift if it happens to you and your Soldiers.

However, do not get lazy. The contemporary operating environment force (COEFOR) has sat at the top of many common operational pictures, surrounded by flashing / screaming personnel and vehicle Multiple Integrated Laser Engagement Systems, listening to a commander attempt to explain why he thought it was OK not to leave the wire when he established his defense. You may think you can see everything from the height of your command post, from your location in your defensive position or from the imagery you’re getting from your Raven / Shadow / Predator feed.

Simply put: You are wrong.

The enemy knows where you are. You’re on his turf.

You cannot adequately execute any of the seven steps of engagement-area development without getting out and walking / studying the terrain. Maps and graphics are excellent tools for planning, and will usually allow you to initiate your priorities of work, but once you hit the ground, it’s time to either confirm or deny your plan and execute or change your course of action. There is only one place at NTC where you should place more than 75 percent trust in a map: in the rotational-unit bivouac area. The terrain is more diverse than you think. The terrain is more diverse than the COEFOR thinks, and the COEFOR has been in more places than most. Get out, walk the terrain, study your dead space. Understand the terrain and its effects. That dead space you identify is more than likely where the “insurgents” or COEFOR are or from where you will first take fire. Identify it and mitigate it. To make it easy, walk / drive the perimeter and talk to each of your positions. Determine where you can observe / be observed, where you can engage / be engaged, where you can do neither, and how to mitigate. Do not be lazy.

Flexibility and mission command

Some would take great advice while listening to a speech from retired COL Douglas MacGregor (S-3 for 2/2 Armored Cavalry Regiment (ACR) during the Battle of 73 Easting): “The key to success in war is to stay so far forward, and to go so fast, that higher command cannot possibly contact you and interrupt your advance.” What sound advice. Yet, when fighting in the box at NTC, we often do not have the luxury of space to break away from our headquarters. Therefore, a key to succeeding in the box is being as flexible as possible. As a company / troop / battery commander, you have to be able to adapt to the ever-changing battlefield and the ever-changing guidance from your higher headquarters.

The key to flexibility is mission command. What mission command means to the COEFOR is to provide our subordinates with clear and concise order and graphics, and then get out of their way to let them fight the fight.

Oftentimes as commanders, we get caught up in developing grandiose orders and the result is: a) wasted time; b) confusion in everyone but you; and c) subordinate leaders focusing too much attention “down” (looking at their notes, orders, mapboards, etc.) instead of looking “out” (fighting the battle in front of them).

Keep your operations orders succinct. Focus on a solid concept of the operation (purpose, form of maneuver or defensive technique, risk, decisive operations, shaping operations, sustaining operations), a simple scheme of maneuver and defined tasks / purposes.

Eliminate the fluff or filler that often accompanies commander’s intent – a bunch of key tasks that are neither key nor tasks – and the hyperbolic endstate. A way to write commander’s intent is in this fashion: here’s what I want you to do, why I want you to do it and why it’s important; here are a few key things we must accomplish to win this battle; and here’s where we need to be at the end of the battle (focused on enemy, terrain, civilians). At the end of the day, if your platoon leaders and other subordinates understood what you are trying to accomplish and why you are trying to accomplish it, the battle will unfold in your favor.

From the tank commander (TC)’s hatch, COEFOR leaders have observed that many rotational units did not execute mission command in this fashion, nor did they have simple orders. It looked as though when making contact, the rotational units stalled as their leadership retraced their complex plans to find how they planned to react – instead of simply reacting.

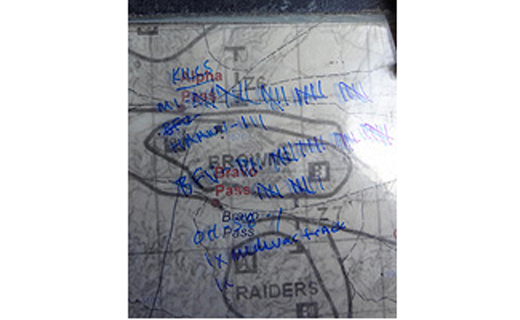

The final piece of advice is about flexibility and not losing on the battlefield at the NTC. This is based on simplicity yet again: have simple graphics and use technology regarding your graphics. In the box, there is no need for a plethora of phase lines, checkpoints and routes. During the movement-to-contact during Rotation 12-05 against 3/3 Infantry Division, which had Delta Company maneuvering the length of the box from west to east, there were seven phase lines. Delta Company also used the on-board technology (FBCB2 / JCR), tying phase lines to grid lines. This goes against conventional wisdom, but the company felt it was much easier for TCs to self-locate and report their positions after a quick look at an easily identifiable phase line on their JCR. Even when there were no JCRs, every TC had a Defense Advanced Global Positioning System Receiver (DAGR). The phase line on a grid line made reporting with a DAGR far easier for the TCs.

The troop commanders assigned a few target reference points tied to easily identifiable pieces of terrain. This enabled an easily understood front that greatly enhanced reporting ability, which greatly enhanced situational awareness.

Much like a simple order, simple graphics allow TCs and leaders to focus their attention outward on the enemy and not downward at their mapboards. By focusing outward, TCs and leaders are able to react to what is unfolding before them – making them flexible leaders, not occupied leaders.

Flexibility is a key to success when fighting on a complex, ever-evolving battlefield. A key component of flexibility is an effective use of mission command. The best way to make mission command work is to focus on simple plans and orders and on simple graphics, and to trust your subordinates to take the fight to the enemy.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook email

email print

print