Battle Analysis: Cavalry Battle at Sailor’s Creek

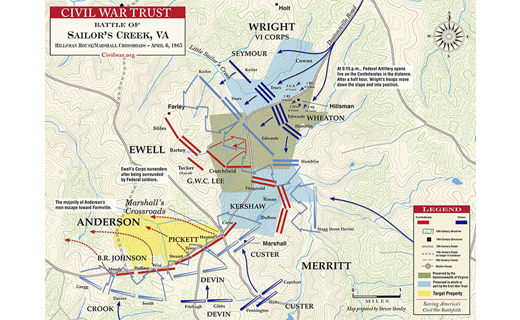

“My God,” said Confederate GEN Robert E. Lee as he watched the Battle of Sailor’s Creek unfold. “Has the army dissolved?”1 In some respects, it had. Union COL Henry Capehart applied reconnaissance fundamentals2 and characteristics of the offense at Sailor’s Creek April 6, 1865 (See Figure 1), to achieve a decisive victory over Lee’s army. The specific characteristics of the offense on which Capehart capitalized were audacity and tempo.

Setting conditions

By April 1, 1865, GEN Ulysses S. Grant and the Union Army were camped east of the road that connected Richmond and Petersburg, VA. Dense fog that morning provided cover for the evacuation of Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia from Richmond. Lee knew that he was outnumbered in manpower three to one and that the Union was about to attack the Confederate capital.3 Confederate President Jefferson Davis authorized the Richmond mayor to peacefully surrender the city to the Union.4 He then relocated the capital to the town of Danville, 145 miles southwest on the North Carolina border.

Petersburg, a supply town with five railroads and advanced road networks about 25 miles south of Richmond, was the next Union prize. Grant believed it held strategic importance if the Confederates surrendered when they ran out of food and supplies.5 In fact, Grant had kept Petersburg under siege for 10 months.6 On April 2, the Union Army attacked the city, slicing through 10 miles of Confederate breastworks, and gained control of the garrisoned resources. Confederate defensive positions did not hold during the massive attack, and Grant’s army captured the city.7 The Union victory at Petersburg forced the Confederate soldiers garrisoned there to evacuate. Since these Confederates desperately needed food, Lee issued orders for all his remaining units at Richmond and Petersburg to link up at Amelia Courthouse, where he believed there were necessary food supplies.8

For the next two days, Grant’s army conducted hit-and-run attacks on Lee’s retiring army as it closed the distance. The Confederates were hungry, exhausted and dirty. MG Philip Sheridan, leader of the Union cavalry, believed the Confederates’ endstate was to refit in Danville. There was a railroad station along their route in Jetersville that could transport Lee’s army directly into Danville. Sheridan understood this, and, on April 3, ordered MG George Crook to send his division to Jetersville and the railroad crossing south of the town near Burkeville. There the Union would set up defensive positions with cavalry and infantry to block Lee’s army from advancing southeast to its objective.9 Crook’s division was dug in to hasty fighting positions by the evening of April 4, waiting for the Confederates to approach.10

Lee’s troops arrived at Amelia Courthouse April 4 expecting to find 350,000 rations. Instead, there were only weapons and ammunition, so he pleaded with the locals to offer what they could to refit his desperate army.11 He ordered his army to move out in 24 hours, which was a dangerous delay because the Union army was catching up to his position. Scouts reported to Lee on the morning of April 5 that the Union had set blocking positions at Jetersville with cavalry and at Burkeville with infantry. Lee knew the route to Danville was impassable and ordered his army to move out along Amelia Road toward Lynchburg.12 The Confederate army moved out April 5 west toward Lynchburg, but the soldiers would have to cross Sailor’s Creek before they reached their destination. It was there the ragged Confederate outfit would meet their match in Sheridan’s favored sons.

Sheridan’s division commanders were BG Thomas Devin, Crook and BG George Custer. Custer commanded 3rd Division with three brigades. His 3rd Brigade commander was Capehart, who commanded cavalry squadrons from West Virginia and New York.13 He was to play the greatest role in thwarting the Confederates at the creek.

In 1861, Capehart had been serving the First West Virginia Cavalry Regiment as regimental surgeon. His leadership during the retreat at the Battle of Mine Run in 1863 had earned him command of the First West Virginia Cavalry Regiment.14 For the next year, he employed sound battle tactics and had trained an aggressive regiment. His soldiers, farmers turned cavalrymen, fought hard and frequently conducted the decisive mission in major battles such as the Third Battle of Winchester. When 3rd Brigade had needed a new commander in September 1864, Sheridan called on Capehart to fill the position.15

Sailor’s Creek

Sailor’s Creek was 57 miles southwest of Richmond, 64 miles west of Petersburg and 100 miles northeast of Danville. The terrain at Sailor’s Creek consisted of rolling hills that progressively declined into a shallow valley next to the creek. There were patches of wooded forests around the area, but large amounts of open farmland dominated the landscape. J. Hott owned one of the farms nearest where the battle occurred. His house was located near a road intersection where the northeast-to-southwest road, called Deatonsville Road, crossed a road that ran due west to Farmville.16, 17

LTG Richard S. Ewell and LTG Richard H. Anderson commanded the two Confederate corps that fought at Sailor’s Creek. Another corps, commanded by LTG James Longstreet, was also part of Lee’s army. Longstreet ordered his corps to continue forward to Lynchburg, creating a five-mile gap between his corps and Anderson’s. Union cavalry established a roadblock in the gap oriented toward Anderson’s direction of advance.18 This forced him to secure defensive positions on the high ground along Danville Road orienting southeast. A third corps, commanded by Ewell, maneuvered into a defensive position on the high ground paralleling Sailor’s Creek on the west bank. It was oriented northeast to defend against the Union’s 6th Corps.

Custer maneuvered his division of mounted cavalry south of the road intersection. At around 7 a.m. April 6, he finally caught up with the rear trains of Lee’s army. He attacked the wagon trains and subsequently captured more than 300 supply wagons and ambulances, in addition to 13 artillery pieces that had never been fired.19 This event set the conditions for Capehart’s decisive engagement later that day. At about the same time, the corps of both Anderson and Ewell could advance no further because of a Union blockade. Their soldiers prepared hasty defensive positions. Custer ordered his men to burn the wagons. Once they were smoldering, Custer’s division continued westward.

The Union blockade on the Danville road forced Anderson to halt his entire formation near Hott’s farm west of Sailor’s Creek. He arrayed his corps along the road, oriented toward the south and southeast toward the creek.20 His brigades used the high ground and temporary entrenchments of rails and earth to their advantage. Confederate soldiers were arrayed three deep, as was customary in European defensive tactics.21 Ewell arrayed his corps along the west bank of Sailor’s Creek. Ewell’s right flank and Anderson’s left did not connect because their haste of setting defenses hindered any coordination. As a result, a large gap existed between the two.22

Leading Custer’s division was Capehart’s 3rd Brigade. The brigade, known as the West Virginia Brigade, was about 1,400 cavalrymen strong. Most were farmers from Pennsylvania or Ohio with significant horse-riding experience.23 At around 2 p.m., Capehart’s brigade approached the gap between Anderson’s corps and Ewell’s corps. This was the first threat contact Capehart had with Anderson’s corps. Understanding the array of enemy forces and identifying the vulnerable gap in the Confederate lines, he developed the situation rapidly and lined up parallel to Anderson’s northeastern-most flank.24 Capehart ordered his regiments into a tactical formation orienting on his objective. Two regiments formed up on-line, spanning a large portion of the battlefield with horse cavalry and Spencer carbines. A third regiment lining up on the right side of the formation was set up in squadron columns to reinforce Capehart’s right flank.25 At this point Capehart was transitioning from conducting reconnaissance to preparing for an offensive attack.

Capehart positioned his third regiment in a squadron column on the brigade’s right flank so he had freedom of maneuver. As mentioned, Anderson’s left flank was not connected to Ewell’s right flank. If Capehart had not reinforced his right flank, the Confederate defenses might have easily defeated his men. Ewell’s right flank could have closed the gap after the West Virginia Brigade had ridden through the lines and counterattacked the rear of Capehart’s formation from two angles, but Capehart did reinforce that right, ensuring freedom of maneuver to retreat to the original Union lines if he needed to.

His entire brigade formation used the rolling terrain to its advantage. As it maneuvered off the road in a northwest direction to approach the gap in the Confederate lines, Capehart used the rolling terrain’s intervisibility lines to cover his approach. He stopped at the maximum effective range of the Spencer carbine carried by his troopers.26 A hill separated Capehart’s cavalry from Anderson’s corps. As Capehart went to reconnoiter the enemy position from atop the hill mass, Custer enthusiastically rode from the Confederate lines toward the West Virginia Brigade carrying Confederate battle flags from their defensive positions. Bullets from Confederate rifles were flying in his general direction of advance. His horse was struck in the chest and collapsed, but Custer was able to safely dismount with the stolen battle flags still in hand.27

Capehart immediately realized the Confederates had to take time to reload their rifles. In an effort to report all information to his superior officer as rapidly as possible, he recommended to Custer that his brigade attack. Custer agreed and ordered the West Virginia Brigade to charge.28 The order to attack was the transition from using fundamentals of reconnaissance to characteristics of the offense. Capehart took his position in front of the formation, with the brigade bugler next to him. Capehart ordered the bugler to sound the attack.29

The cavalrymen put all 1,400 horses into a trot. This was the customary opening speed for a cavalry attack. Immediately, the formation launched the horses into a run, which demonstrated the high tempo, a characteristic of the offense, of the Union attack. Capitalizing on the horses’ speed, Capehart’s cavalrymen, carrying an array of drawn sabers, carbines or Colt revolvers, smashed through the defensive positions and through the three lines of Confederate infantry.30 The West Virginia Brigade’s audacious attack frightened the already demoralized Confederate soldiers, and they threw down their weapons and surrendered to Capehart’s cavalrymen.31

Capehart continued the attack until he was past Anderson’s line and halfway north of Ewell’s positions. The gap between Anderson and Ewell had allowed Capehart to envelop both lines. Unfortunately for the Union, most of Anderson’s corps escaped the battle by retreating northwest to Farmville. However, the First New York Cavalry Regiment, the only non-West Virginia regiment under Capehart’s command, continued its attack to Ewell’s command post. There the cavalrymen captured Ewell and MG Custis Lee. Both sides, in states of confusion, degenerated to hand-to-hand combat. Soldiers picked up rifles to use as clubs. Enlisted Soldiers and officers alike punched and beat others to death on the battlefield.32

Capehart’s West Virginia Cavalry brigade had exploited a gap in the Confederate line, allowing the Union to capture more than 20 percent of Lee’s army. In total, more than 8,000 Confederate soldiers – including eight Confederate generals – were killed or captured.33 Capehart achieved this by employing fundamentals of reconnaissance to gain operational understanding of the situation at Sailor’s Creek. By following the fundamentals, his cavalry brigade gained contact with the Confederate army, developed the situation, identified where to strike the Confederate line and retained freedom of maneuver. The West Virginia Brigade, in true cavalry fashion, easily transitioned from conducting reconnaissance to an offensive attack. Capitalizing on the audacity and tempo that benefited the mobile firepower only horse cavalry afforded, Capehart destroyed the Confederate line.

In this battle, Union cavalry was able to close the distance with a Confederate line that had a significant gap. The gap was a tactical error on part of the Confederate generals in charge. It is impossible to determine if the outcome of the battle would have changed if the Union attacked the gap with infantry instead of cavalry. Cavalry charged at a faster tempo than infantry was able to, so Anderson and Ewell never had enough time to adjust their lines. Horse cavalry had more mobility than infantry. Infantry did not have the destructive effects of a saber and repeating carbine characteristic of a cavalry unit. What history tells us in this battle is that the conditions surrounding both Union and Confederate forces led to a decisive attack by a cavalry brigade. The result of the battle significantly contributed to Lee’s surrender at Appomattox Court House April 9, 1865.

Notes

1Winik, Jay, April 1865: The Month That Saved America, New York: HarperCollins, 2001.

2The fundamentals of reconnaissance are 1) ensuring continuous reconnaissance, 2) not keeping reconnaissance assets in reserve, 3) orienting on the reconnaissance objective, 4) reporting all information rapidly and accurately, 5) retaining freedom of maneuver, 6) gaining and maintaining threat contact and 7) developing the situation.

3Winik.

4Ibid.

5Schultz, Duane, Custer: Lessons in Leadership, New York: Pelgrave Macmillan, 2010.

6Winik.

7Rackliffe, Marjorie, “The Crater,” Cobblestone, Vol. 35 Issue 1, 2014; web.a.ebscohost.com, accessed May 27, 2014.

8Davis, Burke, To Appomattox: Nine April Days 1865, New Jersey: Burford Books, 1959.

9Ibid.

10Ibid.

11Ibid.

12Ibid.

13Humphreys, Andrew, The Virginia Campaign of ’64 and ’65, New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1908.

14Lang, Theodore F., Loyal West Virginia from 1861 to 1865, Baltimore: The Deutch Publishing Co, 1895.

15Ibid.

16Humphreys.

17Editor’s note: The Battle of Sailor’s (also Sayler’s) Creek was actually three engagements: the Battle of Hillsman’s Farm, the Battle of Marshall’s Crossroads (or Battle of Harper’s Farm) and the Battle of Lockett’s Farm (or Battle of Double Bridges). If readers wish to research these battles more, they will not find reference to a “Hott’s Farm” battle. (A good overview can be found at Encyclopedia Virginia’s Website, or descriptions of the Sailor’s Creek battles (and the skirmishes preceding Sailor’s Creek) can be found in a reference such as “The Road to Appomattox” section of Battlefields of the Civil War: A Guide for Travelers, Vol. 2, by Blair Howard.) The Hott farm is described by MG A.A. Humphreys (MG George G. Meade’s chief of staff as well as commander of II Corps, who fought in the battles of Sailor’s Creek) in his book, The Virginia Campaign of ’64 and ’65, as “three miles west of Deatonsville”; near where, early on the morning of April 6, 1865, “Cooke tried to cut off Confederate troops at the forks of the road near Hott’s farm but was repelled by Anderson”; on top of a slope on the north side of Sailor’s Creek; and near the forks where he arrived at about 4:30 p.m. April 6. Although Humphreys devoted these kinds of details to the Hott farm in his book, historians do not refer to it, but the battle Humphreys describes can be inferred as the Battle of Marshall’s Crossroads just by its description of being near a fork in the road. The Hott farm is also notated on Robert Knox Sneden’s map, “The pursuit of the rebel army, April 6-8, 1865, and Battle of Sailor's Creek, Va.” in the Library of Congress’ Civil War maps collection. The three Sailor’s Creek engagements occurred close together; per Howard’s book, Hillsman House is about a mile from Marshall’s Crossroads, which is about three miles from the Lockett farmhouse/Double Bridges site.

18Hendrickson, Robert, The Road to Appomattox, New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 1998.

19Carrol, John M., Custer in the Civil War: His Unfinished Memoirs, San Rafael: Presidio Press, 1977.

20Humphreys.

21Lang.

22Davis.

23Lang.

24Davis.

25Ibid.

26Ibid.

27Ibid. (Editor’s note: Although G.A. Custer was given the credit for the stolen battle flags here, for history’s sake, readers may wish to note that Custer’s brother, Brevet LTC Thomas Ward Custer, was awarded two Medals of Honor; the second was for bravery during the Battle of Sailor’s Creek for capturing Confederate battle flags. T.W. Custer may be meant here, as Carl F. Day notes in Tom Custer: Ride to Glory (University of Oklahoma Press, 2002) that T.W. Custer returned the battle flags to G.A. Custer behind the lines. T.W. Custer was the first soldier to receive the dual Medals of Honor, one of only four soldiers/sailors to receive the dual honor during the Civil War and one of just 19 in history. T.W. Custer perished with his brother at the Battle of the Little Bighorn.)

28Ibid.

29Ibid.

30Ibid.

31Ibid.

32Winik.

33Hendrickson.

email

email print

print