What Our Army Needs is a True Aero Scout

The Army must develop a dedicated, manned aero scout helicopter, designed to support both reconnaissance and security and air-ground combined-arms operations. Also, the aero scout platforms and their pilots must be either organic to or habitually align with the reconnaissance and security (R&S) organizations they support. In spite of the very difficult fiscal constraints our Army is operating under, history and an understanding of potential future conflicts compels us to find a viable solution.

Howze Board

In 1962, the U.S. Army studied its aviation to determine the extent to which ground systems and organizations might be replaced by aviation. The analysis also proposed new organizations and concepts based on an expanded use of aviation. With respect to reconnaissance, the board highlighted the importance of reconnaissance to all operations. It further noted that "integrated ground and air reconnaissance is more effective than pure ground or pure air reconnaissance units." It also affirmed its belief that some missions, including reconnaissance, required "the most intimate coordination with ground combat elements – infantry, tanks and armor – and this coordination, and the responsiveness also necessary, can only be achieved if the pilots are part of and under command of the ground elements, live with them, and operate their aircraft from fields close to the headquarters they serve." (U.S. Army Tactical Mobility Requirements Board (Howze Board), final report, Aug. 20, 1962, Fort Bragg, NC.)

Cavalry squadrons conduct combined-arms, air-ground operations employing appropriate combinations of mounted and dismounted tactics in close contact with the enemy and civilian populace. One of the essential elements of this combined-arms air-ground team is the aero scout. However, Army force-structure changes eliminated our premier R&S organizations: division cavalry squadrons and armored cavalry regiments (ACRs). The elimination of these organizations created separation between our cavalry squadrons and their supporting aviation. Contrary to the Howze Board recommendation, they no longer “are part of and under command of the ground elements, live with them, and operate their aircraft from fields close to the headquarters they serve.”

These changes were originally needed by the growing requirements to support two theaters of operation in Iraq and Afghanistan. The unintended consequence was a loss in our ability to effectively conduct air-ground integration at the lowest tactical level, where it is arguably most important. Put simply, this is a lost art. To anyone who has served in either a division cavalry squadron or legacy ACR, this should come as no surprise. Air-ground integration is a complicated and perishable skill that is only mastered through repetition and training.

Technological advances also contributed to this loss of air-ground proficiency. The relatively rapid growth and assimilation of unmanned aircraft systems (UAS) into our tactical units for operations in Iraq and Afghanistan has given us a false sense of filling the void of air-ground integration. The integration of UAS in lieu of manned aviation platforms originally was a conscious decision based on the flawed premise that technology allowed supremacy in the "quality of firsts" – see first, understand first and act first. UAS systems at all echelons provide outstanding real-time information. Even so, the lack of integration with tactical ground leaders does not support the requirements of these leaders in the fluid and fast-paced execution of their mission.

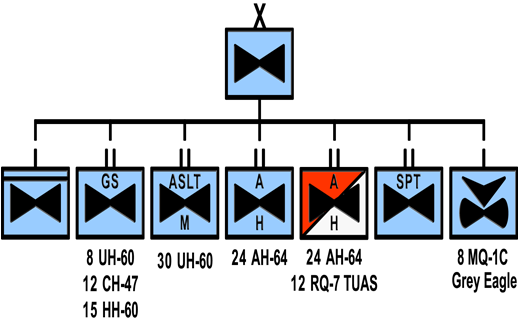

It appears the OH-58 Kiowa Warrior, the Army’s only dedicated rotary-wing reconnaissance platform, will be leaving the Army inventory. In its place, as part of the R&S air-ground team, AH-64 Apache attack helicopters – crewed with former OH-58 Kiowa Warrior pilots at their controls – will serve as our Army’s manned aero scouts. In recent deployments to Afghanistan, AH-64s have teamed with a remotely controlled RQ-7 Shadow tactical unmanned aircraft systems (TUAS), potentially the new "scout weapons team" (SWT). Most Soldiers today recognize the value of the aero scout – both the aircrew and their helicopter. This appreciation for the aero scout and air-ground operations in general is not just a recent trend. Military history describes how the air-ground team has grown in importance and effectiveness over time (see sidebar "Air-ground team development").

AH-64s employed in Iraq and Afghanistan conducted reconnaissance and close-combat-attack missions while flying at altitudes beyond the range of small-arms weapons and at distances that made them difficult to detect. They were able to do this because of their advanced systems, but when the situation dictated, they could still revert to nap-of-the-earth operations. The lack of an enemy integrated air defense permitted these tactics, techniques and procedures (TTPs) in the conduct of counterinsurgency operations. Aerial reconnaissance and surveillance missions were also performed in part by several different models of UASs.

While understanding and applying the lessons-learned from the past 12 years of war, the Army is focusing on our core warfighting abilities. U.S. Army Training and Doctrine Command Pamphlet 525-3-0, The Army Capstone Concept, states: "Countering enemy adaptations and retaining the initiative in future armed conflict will require a balance of forces capable of conducting effective reconnaissance operations, overcoming increasingly sophisticated anti-access technologies, integrating the complementary effect of combined-arms and joint capabilities and performing long-duration area security operations over wide areas." The decisive-action training environment encompasses potential near-peer, hybrid and insurgent adversaries. Given this environment, we can expect Army aviation to face non-permissive environments. This means rotary-wing aircraft will be unable to fly at high altitude and perform reconnaissance and close-combat-attack missions as they were accustomed to doing in Iraq and Afghanistan – and will have to revert to the nap-of-the-earth tactics they flew prior to these conflicts.

Is our Army adequately organized and equipped to perform effective R&S? Employing attack helicopters even though manned with former aero scouts would suggest otherwise and appears to be a step toward creating ad hoc R&S organizations. Our Army's recent organizational trend has been to consolidate manned aircraft in combat aviation brigades while dispersing UASs primarily inside of brigade combat teams (BCTs) and combat aviation brigades. The modular Army split the organic air-ground teams of the division cavalry squadron and ACR. Decreased opportunities to train and operate together requires an aero scout crew and platform that can arrive on-scene with a flexible yet purpose-built set of capabilities readily applied to the situation and easily integrated into the cavalry squadron’s scheme of maneuver. This is very difficult to do in practice.

The Army of Excellence division cavalry squadron and its predecessor ensured integrated air-ground R&S operations by virtue of air cavalry and ground cavalry "living together" in the same squadron. Established air-ground teams understood the capabilities and limitations of their counterparts and how they fought together as a team. Aero scout crews had the skills and experience necessary to land next to a ground scout, leader or commander. Brief face-to-face coordination and information exchanges created synergy and ensured synchronization of information collection, tactical movement and employment of fires. The strengths and weaknesses of the air-ground team complemented each other, providing a synergy and resulting level of force protection and capability far greater than the disparate parts.

The aero scouts of the last 50 years brought terrain-independent movement, speed, tactical agility and depth, the means to facilitate higher-tempo operations and of course, elevated observation. Aero scout aircrews possessed a tactical curiosity honed over time by repetitive reconnaissance and security operations. They grew professionally in a culture that stressed the fact they were scouts who executed their mission in an aerial platform specifically adapted for their mission. This mindset and culture truly set them apart from their attack-helicopter brothers. Aero scout aircrews operated in a "head out of the hatch" manner with maximum peripheral vision – something UAS operators have not replicated with their "soda-straw" view of the battlefield. Linked to ground-control stations, Shadow, Gray Eagle and other similar UAS operators lack the ability to coordinate on the spot or achieve the feel for the situation as aero scout aircrews could.

Likewise, aero scout aircrews communicated directly to the ground-reconnaissance element they were supporting. This is a function we cannot always duplicate with UAS operators, who may be anywhere from two to five echelons above the supported ground force. Even with the use of communications relay and military Internet relay chat, this separation slows the flow of information and coordination, a major detractor to fast-paced reconnaissance and security operations with the purpose to identify opportunities to seize, retain and exploit initiative.

Depending on the enemy situation, the division cavalry squadron's or ACR's air-cavalry troops task-organized aero scout teams or SWTs. When enemy contact was expected, the air-cavalry troop commander normally employed SWTs of OH-58s (hunters) and AH-64s (killers). Naturally, the aero scout(s) in the team conducted area reconnaissance while the "gun" or attack helicopter provided overwatch. The division of labor allowed each to focus on what they did best. Aero scouts agilely flew from point to point across the squadron zone or sector operating where needed forward, on the flanks or over terrain difficult for the ground cavalry to traverse. There was a clear difference in cultures and training between air-cavalry-troop aero scouts and "gun pilots" from attack-helicopter companies. The transition to an AH-64 aircraft as a scout platform has to be all-encompassing, to include culture and training.

With the potential departure of the Kiowa Warrior, the near-term aerial-reconnaissance solution for our force is to employ AH-64 attack helicopters in that role. In some cases, future SWTs will consist of the RQ-7 Shadow TUAS teamed with an AH-64 Apache. Those units will apply reconnaissance-focused mission-essential tasks to improve the capabilities of aircrews and units. The AH-64 manned-unmanned team appears to be the best solution available if we are limited to making current equipment work. But the current configuration of a AH-64-TUAS team doesn't offer up the organic capabilities we've depended on for more than two generations provided by the OH-58 family of aircraft and their "scout" pilots. What our Army needs again is a true aero scout. We require a simple, rugged, agile helicopter with great "eyes," limited armament for a suppressive self-defense capability and communications-compatible with ground elements. Ideally, its armament should be enough to destroy or repel enemy reconnaissance elements when necessary to accomplish doctrinal security tasks.

So what's on the horizon? Well have to wait for the specifics, but the Aviation Center of Excellence lists aerial R&S as a top-tier gap and recognizes a valid requirement for an armed aerial scout. Expect it to also be teamed with UAS.

In all cases, future aero scouts must be interoperable with ground scouts and other ground maneuver elements to accomplish the range of tasks necessary to successful combined-arms air-ground R&S operations. The synergy of air-ground integration will enable mutual support, producing increased effectiveness and improved survivability. Above all, the next generation of aero scouts must also be operated by pilots who retain the soul of a scout.

Similarly, these aero scout formations must enjoy a habitual relationship with the cavalry squadrons they will support. Common understanding of TTPs and standard operating procedures, forged through training exercises at home-station and combat training centers, is critical to achieving this level of understanding and familiarity when employed in combat.

The next aero scout, like the AH-64, must be linked to joint fires to maximize the lethal effectiveness of joint and combined arms at the decisive point. Aero scouts of the future must include select traits of both a fire-support team and a Joint Terminal Attack Controller. The future aero scout will continue to call for fire, conduct reconnaissance for ground maneuver units and attack helicopters, and direct the action of combat aircraft engaged in close air support.

The aero scout's interoperable communications and mission-command tools will enable the aircrew to talk to ground maneuver, fires, intelligence and sustainment elements, other Army aviation elements and, of course, elements of the combined and joint-force air component. The communications suite will include future versions of beyond-line-of-sight communications, including ultra-high-frequency and satellite communications. The aero scout's situational awareness will have to support the multi-faceted joint-fires role as well as its R&S role. A robust navigation capability, combined with an integrated laser range finder/designator, will provide accurate target location for employment of on-board munitions and joint sensors and fires. Mission-command systems should include the next generation of Blue Force Tracker-Joint Battle Command Platform.

Based on Army aviation's recent review of existing commercial-off-the-shelf products, one capable of meeting all the above-mentioned requirements is not readily available. However, capable, affordable solutions are within our reach and should be available within the acquisition timeline. So what are the capabilities we require in the next aero scout? The next aero scout may be a modernized, survivable mix of those essential characteristics embodied by the OH-58 and the OH-6 "Little Bird." Although these two airframes may be beyond their prime, they illustrate some of the critical capabilities of desired characteristics of the next aero scout (see sidebar "Desired characteristics for next aero scout").

Even during times of such fiscal constraint, our Army cannot afford to operate without the capability of effective air-ground teaming. The OH-58D and the cavalry-scout platoon lost much of this capability with the elimination of the division cavalry squadrons and ACRs. While it may not be financially feasible to bring these organizations back, we must find a way to maintain the essential air-ground R&S team capability.

In addition to R&S doctrinal, organizational and materiel solutions, emphasis on training, education and personnel management will help preserve the aero scout. The Aviation Center of Excellence's recognition of aero scout-specific training and leader development are also essential to preserving the desired culture and mindset and will produce critical components of the "total package." The plan to infuse the AH-64 squadrons with former OH-58D scout pilots is a good start to maintaining the skills and essence of the aero scout.

The application of the air-ground team has produced impressive results since its inception 150 years ago. Generations of scouts have since benefited from teaming with the aero scout, and the importance of combined-arms, air-ground R&S operations continues. Whether you are in an R&S BCT, a BCT cavalry squadron or a battalion scout platoon, your ability to conduct R&S operations will be affected by the capability of the aero scouts with whom you operate. Cavalry troopers of the future require and deserve a similar capability. What the Army will continue to need is a true manned aero scout.

email

email print

print